- Extra Points

- Posts

- Let's take another look at the first Heisman race

Let's take another look at the first Heisman race

Good morning, and thanks for spending part of your day with Extra Points.

Before we get to the good stuff, a quick reminder. Because I lost my job at SB Nation last week, I’m making a few changes to Extra Points.

Starting on April 27, Extra Points is switching to a four day a week publishing schedule, rather than twice a week. But two of those newsletters will be behind a paywall. For seven bucks a month, or seventy bucks a year, you can make sure you get access to every single Extra Points newsletter, plus some bonus content (podcasts?).

You can subscribe right here:

I’ll be very upfront here, my goal is to get a base of 150 paying subscribers. That’d be about the level where spending even more time on Extra Points becomes economically viable. If I can exceed 150 subscribers, I can use that extra money to commission posts from other writers. (Do you have a great idea for a newsletter? Pitch me, I’m at [email protected]). Based on your amazing response over the weekend, I think exceeding 150 subscribers is very doable.

I know this is a lousy time to ask for money. If you’re in a tough spot, or if you’re not sure that this project is worth seven bucks, no problem. I’m going to keep writing two free newsletters a week, and I hope you continue to read and enjoy them. But your support makes it easier for me to make that extra phone call, find that extra quote, pay for that Newspapers.com subscription, and just generally, make this project better.

Okay, that’s enough of that. Let’s talk about something that has nothing to do with Covid-19. Lord knows I’m gonna write a bunch more about that.

Let’s talk about the Heisman Trophy. Specifically, the first one.

I understand the prestige and history of the Heisman Trophy demands a certain amount of attention throughout the season, but personally, I usually don’t find the race to be especially compelling. Just like the national championship race, virtually everybody is eliminated before the season begins. To win a Heisman in 2020, you basically need to be the best offensive player (and probably a quarterback) for a big name, national title-contenting team, OR put up absolutely stupid numbers for a nearly Top 20 team. Whenever we play college football again, assuming the Heisman winner will play quarterback or running back at Ohio State, Clemson, Alabama, LSU, Georgia or Oklahoma feels like a pretty safe bet vs the rest of the field.

But that wasn’t always the case. The whole thing used to be a little more interesting. And I think the balloting for the very first trophy makes that clear.

You might remember the guy who won, Jay Berwanger, of the University of Chicago

But I’m guessing you might not know much about the guy.

For one, I think it’s worth pointing out that 1935 Chicago was not the University of Chicago of the early 1900s. Back in the day, Chicago and Michigan were clearly the premier programs in the midwest, if not the country, and it’d be hard to find a school that was more invested (financially or philosophically) in big-time college football than the University of Chicago.

But by 1935, Amos Alonzo Stagg was gone, William Rainey Harper was gone, and the Chicago Maroons, now kneecapped with a smaller enrollment than her peers in the Western Conference, mostly sucked. The Maroons would not finish with a winning record in any season after 1929.

1935 was a high mark for the program, and Chicago only went 4-4, and two of those wins were against “low-major” opponents (Carroll College, of Wisconsin, and Western Michigan). They beat a terrible Wisconsin team by six points, and squeaked by a three-win Illinois team in the season finale by just one. They weren’t especially competitive against any above-average team they faced. This would be like giving the Heisman to a great player on a 6-6 ACC team that needed to beat two FCS squads to make a bowl game in Birmingham. That just doesn’t happen today.

On the field, Berwanger did a little bit of everything. He punted. He was a solid halfback. He threw the ball, and he was a more than capable defender. He’s probably most famous for a) tackling Michigan’s Gerald Ford, yes, that Gerald Ford, so hard that he gave him a scar, and b) for ditching professional football to sell rubber.

So, who did Berwanger beat to win the first Heisman Trophy?

The runner up? That was Monk Meyer of Army

Meyer finished with 29 total points, still well short of Berwanger’s 84.

Monk Meyer was not a large man. A profile in his hometown paper, the Allentown Morning Call, described him as 5’9, 150 pounds. Grantland Rice, who actually covered the guy, described him as “140 pounds of high explosives”. The Uniontown Daily-Herald has him at 5’10, 137 pounds. I assume if I kept googling, I would eventually find a newspaper that describes Meyer as a literal human infant.

Whether the dude was 150 pounds or 15 pounds, it’s clear that his contemporaries thought he was a hell of an athlete. Like Berwanger, Meyer did a little bit of everything, from punting to running to occasionally throwing the football. But unlike Berwanger, Meyer’s Army team was actually good. Army finished 6-2-1 that year, beating a good Yale and Navy teams. They also played in the second most famous game of the year, a 6-6 tie against Notre Dame.

Here’s a great Monk Meyer anecdote from that game, via the Allentown Morning Call:

In telling the story, Monk said he was resting by the locker room doom when someone started knocking on the door. Upon opening the door, Monk was startled to see Notre Dame head coach Elmer Layden, one of the immortal Four Horsemen, along with the Irish players.Layden said “Hey kid, go get Monk Meyer, we want to congratulate him on the great game he played against us.”When the stunned Meyer replied that he was Monk Meyer, Layden continued. “Look kid, we’re not fooling around, we want to talk to Monk Meyer.”Meyer then called over some teammates to verify to Layden that he was indeed Monk Meyer.All the astonished Layden could mutter while looking at the smallish Meyer was “gee whiz”

I’m not sure what would be funnier…if Layden actually said something that wasn’t fit to print in a family newspaper in 1990, or if he actually said gee whiz.

Who finished third? Why, that would be William Shakespeare.

See, I can’t be the only one to think that if they wanted, the troops could get together and beat William Shakespeare in the Heisman Race.

The other William Shakespeare played halfback for Notre Dame, and finished just behind Meyer, with 23 votes. Football Shakespeare claimed to be a relative of playwright Shakespeare, but the football player also had a WAY better nickname. "The Merchant of Menace.” Take THAT, nerd.

1935’s Notre Dame squad was excellent. They finished 7-1-1, with wins over an outstanding Pitt squad, plus victories over USC, Navy, and Kansas.

Outside of the draw against Army, Notre Dame’s biggest game was probably a showdown in Columbus against an excellent Ohio State squad. Local headlines leading up to the game suggest that basically nothing has changed in my old hometown:

In front of a crowd of over 80,000, the heavily favored Buckeyes jumped out to a 13-0 halftime lead, but Notre Dame managed to close the gap to a single point. As time expired, Shakespeare took the ball on what initially appeared to be a reverse but fired a touchdown pass to Wayne Millner to secure the 18-13 upset. This was celebrated as one of the great games, period, in college football history.

So, to recap, a dude named WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE played for one of the most famous teams in America, played in two of that season’s biggest games, had maybe the season’s biggest Heisman Moment, and finished third.

I cannot possibly fathom anything close to this happening today, ESPECIALLY since the guy that won played for a lousy team.

And finally, in fourth, Princeton’s Pepper Constable

The Princeton Tigers finished 9-0, joining Minnesota as the only major colleges to go undefeated. The Tigers didn’t play an especially arduous schedule that year, but they did lay waste against almost everybody they played, and Constable was the engine behind one of the nation’s most productive offenses.

According to his alumni profile, the guy basically could not have been more Ivy League. Via Princeton Alumni Weekly:

In a tweedy collegiate world of Chads, Chips, and Cupes, he was the real deal; his name – honest to God – was W. Pepper Constable Jr. A valuable runner on the 1933 undefeated national champion football team that outscored its opposition 217-8, he then was captain of the again-undefeated national-champion team of 1935 and finished fourth in the Heisman Trophy balloting, the highest of any Tiger other than Dick Kazmaier ’52, and was drafted by the NFL. Pepper had other stews to season, however. A three-time president of his class and winner of the Pyne Prize, he went to Harvard Medical School, served four years as a flight surgeon in World War II, then returned to practice for 20 years in Princeton, where he was chief of medicine at the medical center, a pillar of the growing community.

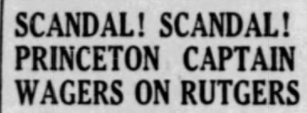

Okay, so being good at uh, basically everything is all very impressive and all…but folks, Pepper has a DARK SIDE. This man, while playing football for the Tigers…bet on Rutgers.

Via the Central New Jersey News, in 1935:

I have no idea if this headline is being sarcastic or not because being on the internet in 2020 has completely broken my brain’s ability to detect irony, but the text of the story suggests that Pepper really was, in fact, betting against his own team?!? ON RUTGERS? Rutgers, who was practically an FCS team in 1935?

In 2020, and correctly so, I think most college football fans and writers are much more numb to stuff that would have been a big scandal decades ago. If a kid makes some money from selling autographs, or because a booster dropped off an envelope of petty cash, only Michigan fans really complain.

But I suspect if we learned that a star athlete was actually betting against his own team, even if it was some sort of weirdo motivational tactic, that player would be the subject of some pretty angry columns. And if that player went to Princeton, well, lol, he’s getting exactly zero benefit of the doubt.

***

Most things in college football, in my humble opinion, really do stay the same. Way back in the mid-1930s, Notre Dame was getting the most press attention, Ohio State played in the biggest game of the season, the Ivy league guy was doing something shady with his money, you know the drill.

But this race really stood out to me as a rare exception. The Heisman champion was a player on an average-at-best squad without eye-popping counting stats. Winning the award itself wasn’t even that big a deal. Berwanger would recount that he was more excited about the trip to New York than the award itself and that it didn’t provide much social cachet on campus. The runner-up was an undersized kid at Army.

In a few years, everything would change. Chicago’s football team would have both feet in the grave, nearly ready to exit intercollegiate sports entirely. Many Ivy League institutions were on their way out of big-time football as well. The idea that a winner of a national college football award would opt for a career in manufacturing or sales, rather than anything football related, would become a foreign one.

Sometimes, it’s fun to look back and remember that actually, even though we’re arguing about a lot of the same stuff folks argued about 100 years ago, a lot of college football stuff still has changed quite a bit.

I mean, I can promise you this. Now that we have the internet, if we have another P5 superstar named William Shakespeare, we are never, NEVER going to hear the end of it.

Thanks again for supporting Extra Points. Now, more than ever, your readership, and your support be it emotional or financial, makes this project possible. Article ideas, story pitches, comments, questions and more can be sent to [email protected]. And if you enjoyed this newsletter or other newsletters, please consider sharing them with your friends.

Join the conversation