Good morning, and thanks for spending part of your day with Extra Points.

I have some exciting announcements before we get to the story today.

1) If you would like some Extra Points stickers, but didn’t snag any last week, good news! They’re now for sale. You can get both stickers for just $5, and shipping is free.

You get the adorable FOIA Saxa bulldog, and the old time-y EP baseball cap script. I think they look great on laptops, water bottles, and varied other flat surfaces.

2) On this week’s episode of The Intercollegiate Podcast, Daniel speaks with former college distance running champion Victoria Jackson, who now teaches sports history at Arizona State. Jackson has, over the last year, written several, attention-grabbing op-eds about college sports reform, including one in the Boston Globe last month, which argued that the upcoming college football should be canceled for reasons having nothing to do with the pandemic. Jackson talks about how her reformist impulse was ignited by watching the 2011 Carrier Classic; how she reconciles her own “privilege” as a former athlete competing in a non-revenue generating sport; and what hope might be gleaned from the latest Senate hearing on NIL and athlete compensation rights.

3) The best way to support Extra Points and The Intercollegiate is through a paid newsletter subscription, which gets you four issues a week, instead of just two. Subscriptions cost just $7 per month, or $70 for the entire year. I also offer really big discounts on bulk orders, especially for our friends with .edu email addresses. If you are interested in getting subscriptions for multiple people, drop me an email at [email protected] and I’ll take care of you.

Over the past few days, paid subscribers got to read stories about how the cancellation of sports impacts school’s ability to charge athletes fees, how America has produced elite college-aged athletes without the NCAA or college sports, how the NAIA plans to navigate the NIL debate, and more.

Okay! Let’s talk about everyone’s favorite thing about college athletics: contract law!

How do you get out of a college sports contract in a pandemic?

By Matt Brown and Daniel Libit

Last month, UC Berkeley hired Chelsea Spencer, a former Golden Bears shortstop during their successive College World Series runs of the early aughts, as the school’s new head softball coach.

“Chelsea's passion and enthusiasm for Cal and Cal softball continues to shine through,” Athletic Director Jim Knowlton said upon Spencer’s hiring. “She brings a well thought-out, data driven approach to the game and has a clear vision for the future of the program.”

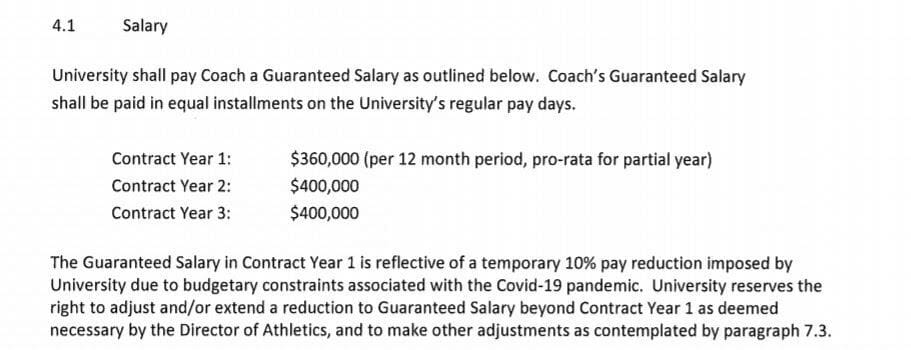

But the $195,000-per-year contract Spencer signed on June 9, which we obtained through a public records request, reflected a much foggier vision for the future of the program she was now inheriting, mid-pandemic:

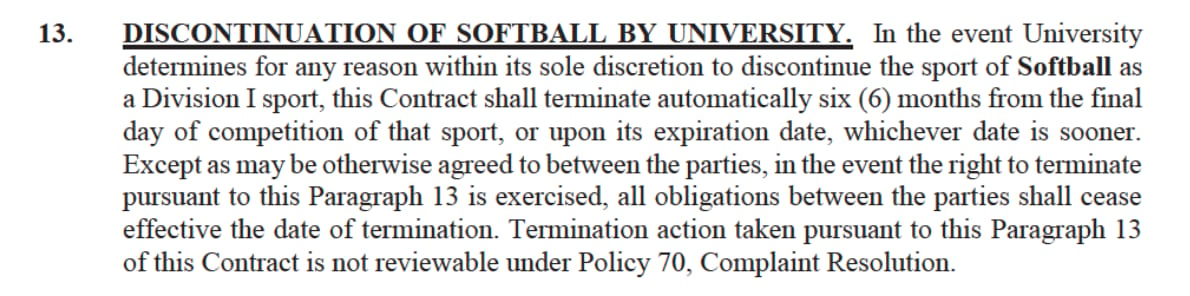

Almost as soon as the NCAA canceled March Madness, college athletic departments (and their schools’ general counsel offices) were confronted by the reality that many of their athletic agreements didn’t include language that scaled to the new realities of the world. Over the last four months, as their budgets have been squeezed by the financial recession, university lawyers have been given another opportunity, desperately needed in many circumstances, to draft some new lines of fine print if not entire subsections. Meanwhile, we’ve been trying to keep tabs through public records requests of coaching and game contracts.

By now, there’s a decent chance you’ve Googled the French phrase, “force majeure,” at least once

In case you haven’t, force majeure refers to unforeseeable circumstances that would make it impossible to execute a contract. As athletic contests are being canceled left and right, it’s suddenly a very important legal consideration: what should schools be paying — to other schools; to their athletic department staff — if games aren’t being played?

If a football game getting canceled due to concerns over COVID qualifies as a triggering force majeure event, then nobody is owed any cancellation fees. If it doesn’t, well, some big schools are going to be obligated to pay some smaller schools a lot of money.

So, does it? Here we find ourselves mired in the conditional: It depends, at least in part, on state laws, on what local governments do (did the governor make you cancel the game, or did you reach that conclusion on your own, for example), and perhaps most importantly, on the specific contract itself.

Take this clause from Ohio State’s contract to host Bowling Green this season. This agreement was signed back in 2016, well before most Americans knew what coronavirus was (but right amidst a series of near-misses with avian flu):

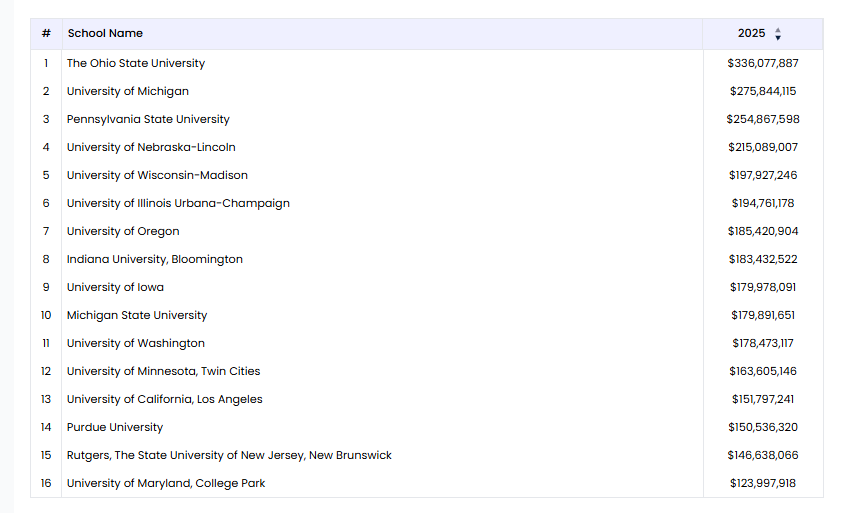

All sorts of potential calamities are mentioned here, but conspicuously absent is any mention of an outbreak or pandemic. Is COVID an unforeseen catastrophe beyond the control of either party? That will depend on the interpretation of folks who charge a lot more than $7/mo or $70/year for insights. Several sports lawyers working in and around college athletics tell us that in practice, it’s a more complicated question than what a common-sense reading of that above-referenced passage might imply.

But to be fair to Ohio State and Bowling Green, nobody who creates athletic contracts now was alive the last time a mass outbreak event potentially threatened college football on a large-scale level. Games get canceled or postponed due to crazy weather just about every season. Power failures happen. Shoot, game delay on account of war happened more recently than the last mass outbreak. So we can understand why maybe adding in some hedging verbiage about an economy-stopping severe acute respiratory virus may have slipped their minds.

But what about contracts signed after COVID entered the public consciousness? Are those being updated to account for pandemics?

We haven’t seen every single contract, but based on what we’ve had a chance to see, the answer is clearly, “not as often as they should.”

To that point, here’s University of Louisville sports law professor Anita Moorman:

The answer, revealed later in that tweet thread, was three.

Here’s an example of a force majeure clause among recent game contracts we’ve FOIA’d: Utah State’s agreement to play at Mississippi State in 2024. The contract was signed on May 20, the same day the World Health Organization reported the largest single-day spike (at that time) in global COVID cases.

This language seems to cover virtually every single possible reason for canceling a game except for a pandemic!

On the other hand, here’s an example we found of a school explicitly mentioning pandemics —Miami of Ohio’s agreement to play football at Wisconsin in 2025 — which was also agreed to this past May:

What about coaching contracts?

Financial instability (who the hell wants to be stuck paying a buyout, now?) dramatically slowed the coaching carousel in major sports. Out of all the Power Six (the P5 plus the Big East) conferences, only one school, Wake Forest, fired its men’s basketball coach this off-season. It’s unusual for FBS head coaches to leave their jobs during the late spring and summer under normal circumstances, let alone these.

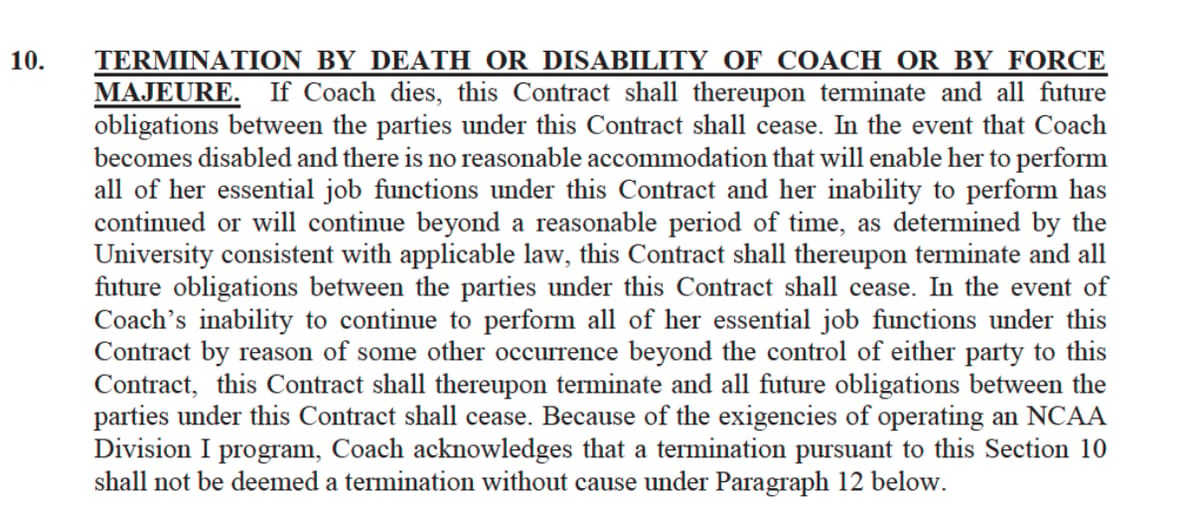

Up until recent times, it’s been rare for universities to include force majeure language in coaching contracts, although it appears that Cal is one of the schools that has done so.

Chelsea Spencer’s current agreement mimics the language found in head football coach’s Justin Wilcox’s contract from 2017:

It’s worth noting how nondescript the act-of-God stipulation is: “by reason of some other occurrence beyond the control of either party.” That could mean a lot of different things!

The University of Houston has included only incrementally more specific force majeure language in its coaching contracts. For example, here’s what we found towards the bottom of head men’s basketball coach Kelvin Sampson’s:

When we showed this to a sports agent who represents a number of college coaches (but not Sampson), he said that while the clause gives UH an out, “it’s really sloppy” and hard to “know what that triggering event looks like.”

That said, these contracts represent outliers in the sea of college coaching agreements, which don’t even contemplate withholding monies from coaches in the event their sports seasons are canceled.

But perhaps that will soon change.

Consider the University of Oregon, which didn’t leave anything to chance in its hiring of wide receivers coach Bryan McClendon.

Oregon economics professor Bill Harbaugh, who runs the excellent, muckraking public records blog, UOMatters.com, recently flagged some unusually specific opt-out conditions in the deal McClendon inked back in April.

First, there are explicit COVID-19 “constraints” to his annual salary:

Like a lot of coaches across the country, McClendon’s pay is being docked as the department tries to navigate a world where COVID dramatically decreases revenues. If revenues continue to decline, the athletic director has the ability to extend those cuts.

But it was this clause, a little later in the contract, that was really eye-catching:

Almost every major college has furloughed at least some staff over the last several months. But while negotiating pay cuts for high earners in an athletic department hasn’t been unusual, actually furloughing a coach remains exceedingly rare. Boise State furloughed coaches. West Virginia furloughed some athletic staffers, as have other schools, but to the best of our knowledge, nobody else in FBS actually furloughed football coaches.

The distinction between a pay cut and a furlough is an important one. When you’re furloughed, you can’t work. Those are days you’re not supposed to be contacting recruits, accessing your university email, or doing any other work-related activities. If your pay is cut, you can still go about your business as normal.

One sports lawyer we spoke to said that’s exactly why many schools have been reluctant to furlough their coaches. There’s also a question as to whether a school could actually impose a furlough: state law and individual contracts may prevent this when it comes to university employees under contract, such as a football coach, as opposed to those that are at-will.

If a university is going to interrupt academic research, instruction, and core university staff work, it’s probably fair for them to also interrupt athletic work — especially if a pandemic forces the cancellation of games.

These sorts of clauses could give universities more financial flexibility, just in case, God forbid, we’re ever in an act-of-God situation again. They may also be an impetus for schools to begin clawing back a little bit of power in the increasingly one-sided deal-making over college coaching salaries. Adjuncts typically don’t get buyouts, after all.

Protecting yourself in the fine-print of contracts is why lawyers get paid. But before litigation, there’s negotiation

Suing people is expensive, time-consuming, and relationship-damaging. Given how insular the college sports industry is, there are pretty strong incentives for parties to try to settle their disputes outside a courtroom. (Unless, say, you’re Bret Bielema.)

That’s especially true in the case of game contracts. Many of these smaller schools, like those in the MAC or Big Sky, may very well have the law on their side, should they seek damages from larger schools who cancel football games. But it’s also in their best interest to maintain positive, working relationships with those larger schools, which effectively serve as their guarantors. The small schools need big, early-season paydays to fund the rest of their seasons; athletic staffers at the small schools likely aspire to one day work at those larger schools; and the ultimate leverage in the working relationship is with the big institution. Ohio State doesn’t have to schedule Bowling Green, after all. They went decades without doing it before.

It’s likely more mid-major schools would be inclined to seek a settlement over canceled games (perhaps taking a portion of the fee owed and a raincheck for a future date), over acrimonious and drawn-out court battles. The pandemic has backlogged the nation’s civil courts, just like everything else, so even a successful litigation could take years to be resolved. After all, for many mid-majors, the anticipated money for future pay-day games has likely already been spent.

But you put yourself in the best position possible to navigate those conversations by having a strong, protective contract. If schools aren’t doing that now, they ought to make changes before they sign that next football game agreement –– or extend their head coach.

Who knows what SimCity2000 disaster will strike next?

Maybe schools ought to throw in clauses about volcano eruptions or monster invasions. Just in case.

Thanks for supporting Extra Points. If you enjoyed this story, why not share it with a friend? FOIA’d game and coach contracts, story ideas, questions, comments and business inquiries can be sent to Matt at [email protected], or to @MattBrownEP. You can reach Daniel at [email protected] and @daniellibit.

The Intercollegiate and Extra Points are proud to partner with the College Sport Research Institute, an academic center housed within the Department of Sport and Entertainment Management at the University of South Carolina. CSRI’s mission is to encourage and support interdisciplinary and inter-university collaborative college-sport research, serve as a research consortium for college-sport researchers from across the United States, and disseminate college-sport research results to academics, college-sport practitioners and the general public. You can learn more by visiting CSRI’s website.