Good morning, and thanks for spending part of your day with Extra Points.

Easy NIL for EVERY athlete in EVERY sport

NIL is changing the economics for student-athletes, but 85 percent of NCAA athletes are being left behind. Along with millions of sports fans.

That’s why we built FanSpark — a brand new, sports-only subscription content platform where every athlete in every sport can build a massive new fan-powered NIL revenue stream.

FanSpark is simple:

Athletes post exclusive social content for their fans

Fans and alumni pay a monthly subscription for that content

Athletes get 80% of the revenue, FanSpark gets 20%

Athletes retain full ownership and total control over their content, brand, and image

NO DMs, NO pay-per-view content, NO betting, and NO tips — just athletes and sports content

FanSpark is a game-changer for athletes in every sport, especially Olympic and so-called “non-revenue” sports that struggle with NIL opportunities.

Set up a quick 15-minute call to see FanSpark in action, and learn how it can benefit every student-athlete at your school.

I file a lot of open records requests here at Extra Points. Some of those are requests are for newsgathering maintenance, like MFRS reports, AD contracts and head coaching contracts — the sort of documents I’ll refer to regularly in my own reporting. And some are vendor contract requests that we use for the Extra Points Library. I’ll file for stuff I’m trying to better understand (so if you get a request for conference bylaws or for rental agreements for off-campus stadiums … that’s why).

And I’ll file for information for ongoing or potential stories, like our stadium alcohol tracker, which way more fans than I expected seem invested in. (I’ll share updates on the October numbers once I have more specifics, but right now, all I can really tell you is that Southern Illinois has sold more alcohol than Western Illinois so far. Surprise!)

One thing I haven’t done a lot FOIAing for — at least, not recently: athletic department revenue sharing numbers.

That isn’t because I’m not interested in those figures. On the contrary, I am very interested in basically any sort of financial information surrounding House payments, athlete contracts and revenue sharing. I have a few blank contracts for House payments in our Library, but right now, that’s about it.

Our previous attempts to obtain virtually anything related to athlete payments have not been successful, with the schools I’ve FOIA’d hiding either behind FERPA, trade secrets or competitive harm clauses. I figured we were not sufficiently lawyered up to change any minds, so I decided to focus more of my efforts elsewhere.

Thankfully, not everybody gives up so easily. My old pal Daniel Libit over at Sportico has continued to fight the good fight for financial disclosures:

Only two of the dozen or more schools I’ve asked—the University of Kentucky and the University of Colorado—were willing to share even top-line totals and transactions of what they had distributed. Although the University of Texas had previously disclosed what it spent in the month of July ($1,603,253.18), it subsequently declined to provide its spending through September.

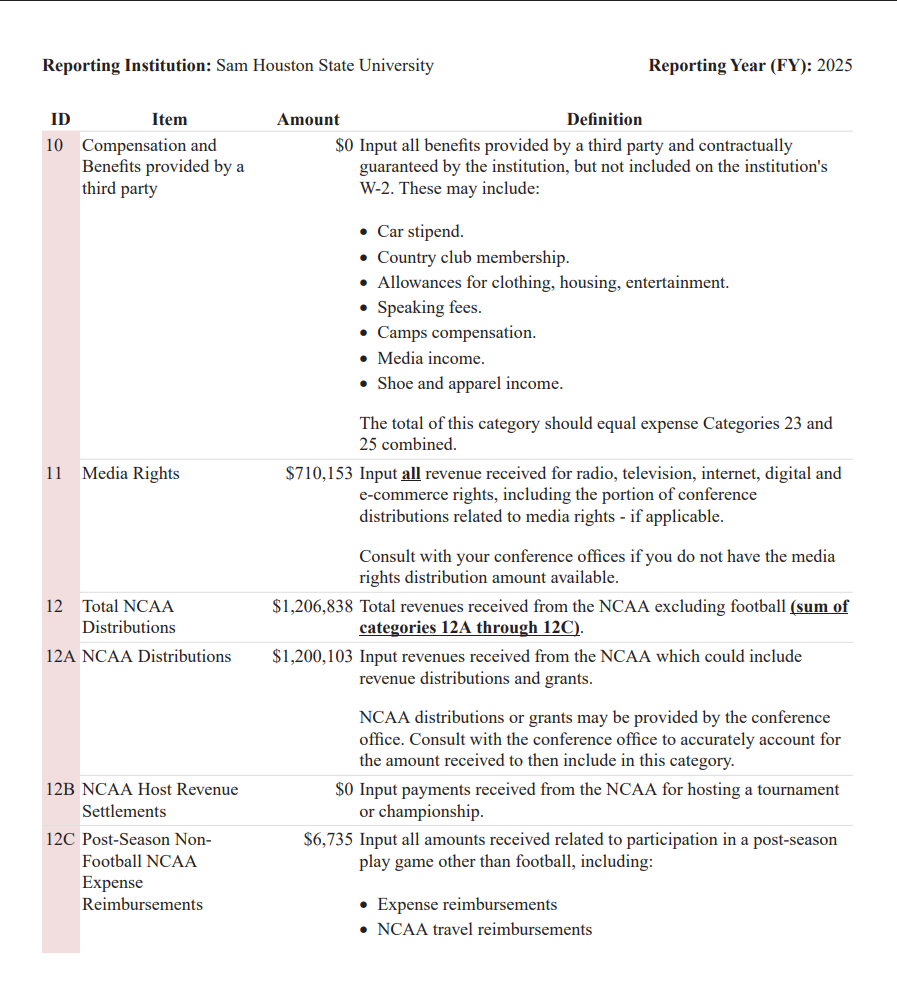

No school was willing to provide anything more granular, except by way of excuses. Curiously, at least a couple schools I petitioned, including Texas A&M and Wisconsin, claimed they possessed no records revealing the information I sought—a puzzling assertion that raises the question of how they then plan to provide this data as part of the NCAA’s updated membership financial reporting services process.

…

For the record, in the first three months of the House revenue-share era, Kentucky made 98 payments to athletes totaling $1,486,099.20 and Colorado made 262 payments for $7,672,052.88. So there it is: Wildcats and Buffs fans are now free to blame me for whatever competitive harm may come.

Libit’s reporting makes me want to take another whack at filing these requests, perhaps for a different set of schools than my national media peers.

The only argument against releasing any sort of athlete financial data that I find even a little bit persuasive is the idea that college athletes are uniquely vulnerable to harassment from fans and gambling interests, should their compensation be made public … in a way that coaches, senior athletic department staff members and non-athletic employees might not be.

Now, I don’t find that argument persuasive enough to forbid financial disclosures completely — but I could see a world where it might make sense to limit disclosures to data sets that couldn’t be connected to any single specific athlete (like how much money a school has committed to spend, or on what sports), at least until society gets better at regulating gambling.

But beyond that, I really agree with what Libit argued in September. A lack of disclosure from schools doesn’t just fly in the face of the letter and spirit of most open records legislation; it actually hurts the players. From his editorial:

“Without transparency,” it states, “no one—including female student-athletes themselves—has any idea whether UNM’s distribution of revenue-sharing payments provides female student-athletes equitable opportunities or equitable treatment between genders as required under Title IX.”

It’s not just about fairness for women. Male football and basketball players, who will receive the largest shares of House money, should also support public access. Transparency allows all athletes to see not only how much their counterparts at other schools are earning–without having to rely on aggregated from vested third parties like Deloitte or Opendorse–but also to understand the full terms of those deals. It stands to reason that this kind of visibility leads to more informed, strategic, and equitable negotiations.

In my previous employment experience, the loudest voices protesting compensation disclosures were usually management, not labor. If everybody in a company suddenly found out what everybody else is making, well, people might start agitating for more money! It would make management’s life harder! Unions regularly fight for increased pay transparency, not less.

Right now, the entity with the biggest advantage in any college athletic labor negotiations (and that’s what these House payments are, not Instagram influencer contracts … be for real) is the one that has the most information. And the entity that usually has the most info right now? It isn’t the athletic directors or general managers; it’s (competent) agents, folks who have to have a working knowledge of budgets across multiple schools.

Everybody else is basically comparing notes they get second- or third-hand … be that the data brokers who have a professional interest in one of the negotiating parties, reporters who hear enough whispers to try and sketch out some compensation ranges, or GMs who compare notes but are self-interested enough to hold some stuff back.

The more of this information is public, the more that players and schools can more efficiently figure out how to value one another’s services — and the less effective whisper campaigns will be.

Is one school asking athletes to sign hysterically one-sided contracts? Forget the rumor mill, release the contract, and let’s see how one-sided it actually is. Are schools backloading contracts, ABA-style, so the top-line numbers look way bigger than the actual cash distributed? If a coach is pleading to his or her AD to increase a soccer budget, because everybody else in the league is throwing NIL money at their rosters now — well, how is anybody to know for sure?

Right now, you can’t. The more data schools are willing to disclose, the more efficient the market will be.

If “competitive harm” is truly the legal and policy justification, then coach and vendor contracts shouldn’t be made public either. Lord knows schools (and agents) try to poach coaches all the time, and a clever FOIA-er can figure out all sorts of competitive pricing intelligence from vendor contracts.

But we allow that disclosure, because it’s the right thing to do for taxpayers, the university community and, ultimately, even the industry.

If I can file a FOIA and learn what a school pays an undergraduate cafeteria worker, a $10 million head coach and every single other employee of an athletic department … I struggle to see why admitting you’re spending $13 million on football instead of $11.5 million is some sacred state secret that must be kept hidden.

I can be blamed for a lot of stuff … but I’m not the reason anyone’s football team lost last weekend, and I won’t be the reason anybody loses in the future if I end up publishing some financial disclosure forms over the next few months.

Now, if you’ll excuse me, I need to get back to doing the people’s business: calculating how many hot dogs per scanned tickets were sold at New Mexico State so far this season.