Good morning, and thanks for spending part of your day with Extra Points.

Thanks to everybody who has played Athletic Director Simulator 3000 since we formally released it two weeks ago. Based on your feedback, we’ve already pushed a few updates (such as allowing users to play multiple ‘seasons’ as a high major in order to get higher scores, slowing down the text speed, etc), and added several more questions. ADS3000 is available for all of our D1.classroom partners and Premium Extra Points subscribers. We’ll be pushing out more updates this week, so it’ll be worth firing up the game again every few days!

I’m happy to pass the mic over to a longtime member of the D1.ticker extended cinematic universe, Dr. Steve Dittmore, the dean of the College of Education and Health Sciences at Baldwin Wallace University. Dr.Dittmore and I have chatted for months about the types of schools that expand their sports programs not in hopes of winning more championships or earning more TV revenue…but in recruiting and retaining students.

You might have missed this, but since 2020, nearly two dozen colleges with athletic departments have straight up closed. Why? Did those schools have anything in common? Why didn’t their athletic department offerings help stave off enrollment decline?

I’ll turn the time over to Dr.Dittmore here:

Since the pandemic briefly shut down in-person higher education in March 2020, 20 four-year campuses, by my count, have completely shuttered operations. This includes one of the most recent, Cabrini University, which will close following the 2023-24 academic year. At least six additional universities have remained open but ended their athletic programs. None of the schools that closed compete in Division I, although St. Francis College (NY) did drop athletics.

I have written a fair amount in this space about the trends in adding and dropping sports since the pandemic. For some universities struggling with enrollment, adding sports makes sense, even on DI campuses. Xavier University athletic director Greg Christopher recently told the Cincinnati Enquirer,

“Athletics is not the most important thing Xavier does, but it may be the most visible. Xavier is an enrollment-driven institution. As we were going through the process (of adding lacrosse), we came to the realization that our 19 sports are almost entirely net-revenue positive to our institution – the tuition (athletes) pay, room and board.”

While I stand behind the overall strategy of colleges providing students opportunities to further their identities in extracurricular activities, everything from sports to performing arts, the news that Villanova University was buying its neighbor Cabrini, just four years removed from a DIII men’s lacrosse championship, forced me to pause and wonder,

What happens when sports does not work for a campus?

Those 20 schools to cease operations were, in order they announced they were closing or being purchased:

MacMurray College (IL) announced 3/27/20 = 14 DIII sports

Urbana University (OH) announced 4/21/20 = 17 DII sports

Holy Family College (WI) announced 5/4/20 = 9 NAIA sports

JWU Denver (CO) announced 6/26/20 = 15 DIII sports

Concordia College (NY) announced 1/28/21 = 12 DII sports (sold to Iona)

Wesley College (DE) announced 2/15/21 = 17 DIII sports (sold to Delaware State)

Mills College (CA) announced 3/18/21 = 6 DIII sports (sold to Northeastern University)

Becker College (MA) announced 3/29/21 = 13 DIII sports

Ohio Valley University (WV) announced 12/9/21 = 14 NAIA sports

Lincoln College (IL) announced 3/29/22 = 21 NAIA sports

University of the Sciences (PA) announced 6/9/22 = 14 DII sports (sold to Saint Joseph’s)

Holy Names University (CA) announced 11/21/22 = 13 DII sports

Cazenovia College (NY) announced 12/7/22 = 17 DIII sports

Presentation College (SD) announced 1/17/23 = 8 NAIA sports

Finlandia University (MI) announced 3/2/23 = 13 DIII sports

Iowa Wesleyan College (IA) announced 3/28/23 = 19 NAIA sports

Cardinal Stritch University (WI) announced 4/10/23 = 15 NAIA sports

Medaille University (NY) announced 5/15/23 = 20 DIII sports

Cabrini University (PA) announced 6/23/23 = 18 DIII sports (sold to Villanova)

Alliance University (NY), formerly Nyack College, announced 7/1/23 = 14 DII sports

A total of 289 sports teams, an average of 14.5 per school, were eliminated. Nine schools competed at the NCAA Division III level, while five universities competed in NCAA Division II. Six institutions were NAIA members. From a trend standpoint, eight schools announced their decisions within the first 13 months of the pandemic (March 2020-2021). A period of relative stability followed, buoyed in many cases by CARES money. However, during the most recent half year, from November 2022 through July 2023, nine schools, four at the Division III level, confirmed their plans to close.

What happened? That is a tough question to answer with generalities as each university’s story is its own worthwhile case study. But what if we could use some common data points to provide insight into similar characteristics of the most recent member campuses that were forced to close?

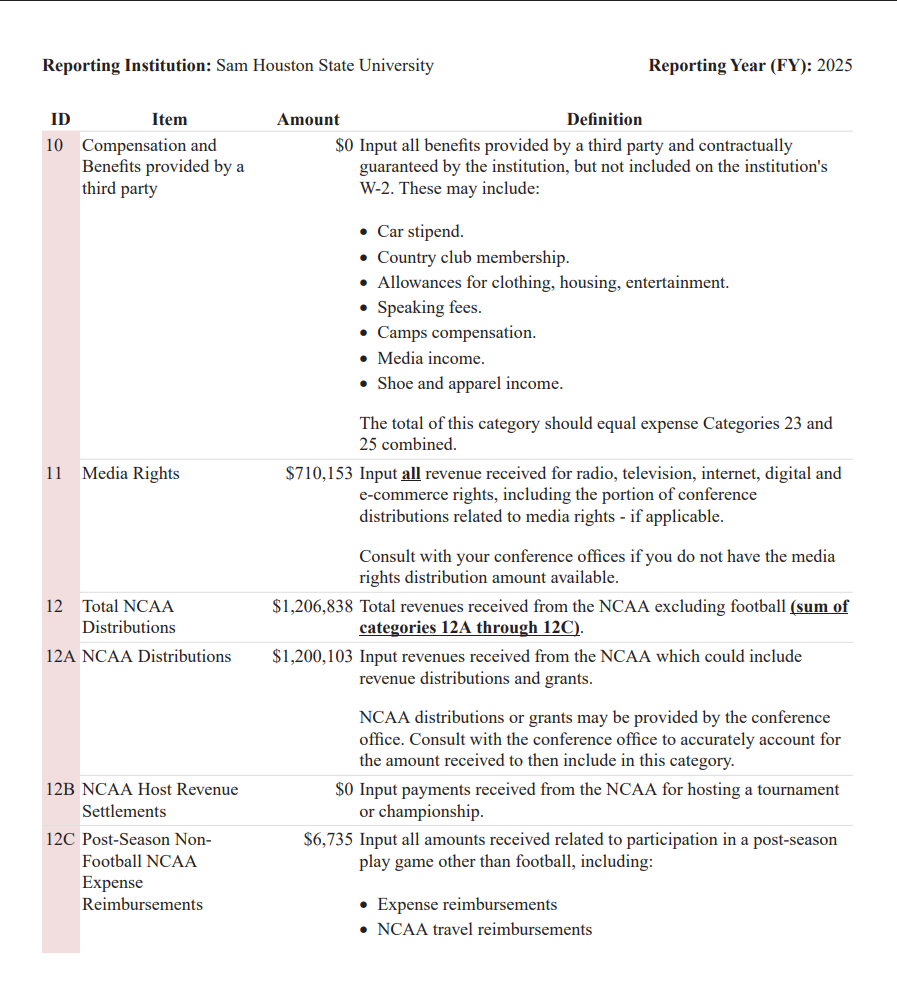

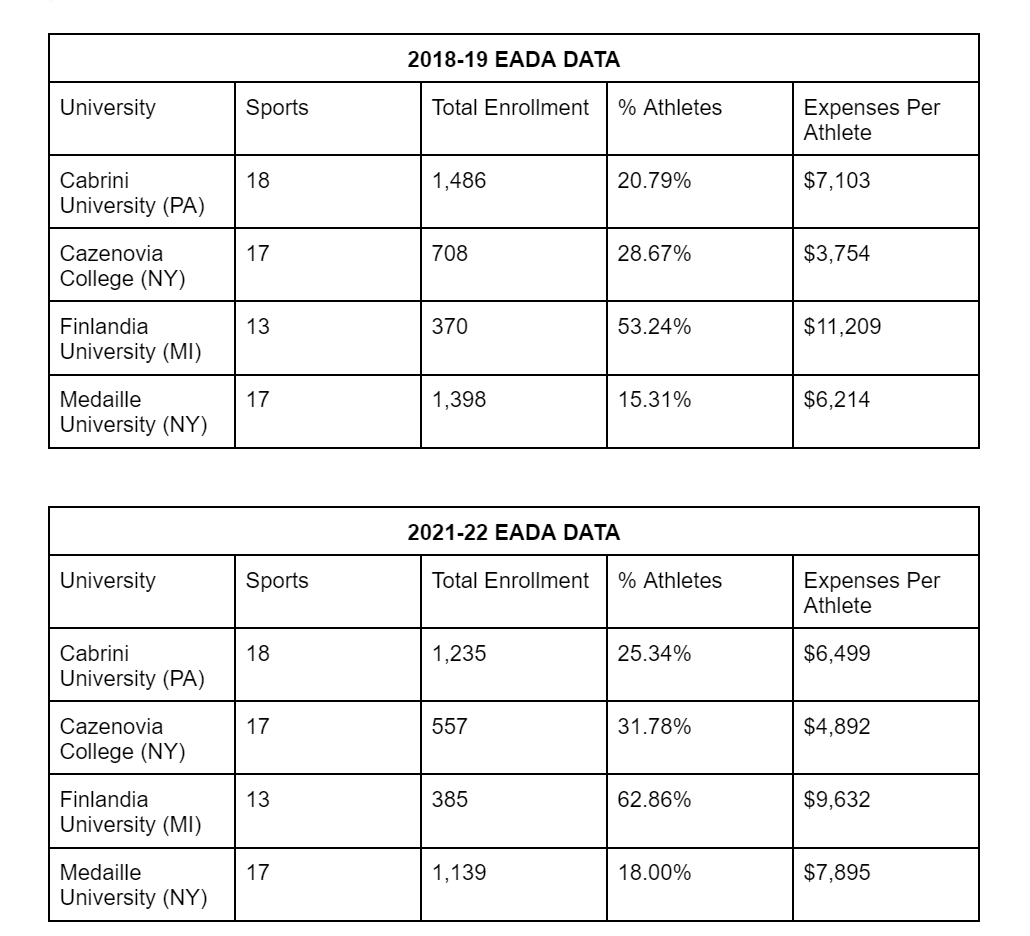

Considering ONLY data as reported to the Office of Postsecondary Education, here is a snapshot of the four DIII universities which announced, since December 2022, they will be ceasing operations. I focused on reported campus enrollment, unduplicated participant headcounts, and reported total expenses. The first chart shows Equity in Athletics Disclosure Act (EADA) data from 2018-19, the year before the pandemic, while the second chart shows EADA data from each school’s most recent filing from 2021-22. To obtain expenses per athlete, I divided the total expenses by the reported number of unduplicated participants.

These two tables do not come anywhere close to presenting a full picture of what transpired at these institutions. As such, inferences drawn from this small data set should be considered anecdotal at best. That said, we can find some additional insight in a deeper dive into the data.

Finlandia University reported $2.3 million in expenses in 2021-22, the largest in our sample, while Cabrini University reported $2.1 million. Medaille University reported $1.6 million with Cazenovia College reporting just $866,000. That’s P5 offensive coordinator money.

The four universities lost, on average, 161.5 enrolled students during this period. Medaille (-259, or 18.5%) and Cabrini (-251, or 16.9%) experienced the deepest declines by headcount, while Cazenovia suffered the highest percentage drop at 21.3%. Finlandia actually observed a slight increase of plus-15 students.

Many Division III institutions are tuition-dependent, meaning they rely almost exclusively on students enrolling on their campuses and paying tuition to operate.

These same institutions frequently increase the number of extracurricular activities they offer as a way of enticing students to attend. Additionally, with no roster caps, many coaches are encouraged by their athletic directors, sometimes at the behest of campus administration, to “offer” additional roster spots to players creating, in some instances, bloated roster sizes.

While three of the four campuses were combatting steep losses in student headcount, the percentage of student-athletes on those campuses did not mirror these changes. All four institutions saw their percentage of student-athletes rise during this period and student-athlete headcount did not match enrollment change as the two tables below point out.

This is not to suggest that I have first-hand knowledge - I do not - that any of these four schools deliberately inflated roster sizes in order to stabilize enrollment. But it is worth examining, at least anecdotally, how roster management might have worked at these schools.

The four institutions in this sample sponsored a wide variety of sports from ice hockey to football to lacrosse to field hockey. In an attempt to find a common denominator, I used men’s and women’s soccer rosters, one of the few sports sponsored by all four schools. I accessed each school’s athletic website on July 1, 2023 and counted the number of athletes listed on the men’s and women’s soccer rosters for 2018 and 2021.

Cabrini grew by 10 soccer players, six men and four women, between its 2018 and 2021 rosters while Finlandia grew by 18 players, 15 men and three women. Cazenovia, which experienced the greatest percentage of overall enrollment decline, still grew its soccer rosters by one player for each team. Medaille, which lost the greatest total number of students at 259, only decreased by two total players, one for each team.

Even as the overall number of students on campus was dropping, only Cabrini exhibited a decline in overall athletic spending. Medaille actually reported an increase of $288,670.

On April 11, 2023, Birmingham-Southern College (BSC) had the top ranked Division III baseball team (it finished 15th in the final poll). Simultaneously, the university administration was appealing to the Alabama state legislature for a $37.5 million lifeline in order to avoid closing its doors. Its board ultimately voted to remain open into next year, helping the campus avoid, at least temporarily, the fate of the other four.

Per its EADA report from 2021-22, BSC had an enrollment of 1,039 students with 483 (46.5%) playing a sport. Of its 504 male students, 63.1% participated in a sport, including 123 on its football roster, nearly a quarter of the campus’ male population. Baseball was second with 45 participants. With $8,778 spent per participant overall, BSC was investing more per athlete than three of the four universities that closed.

In 2018-29, BSC reported 1,260 students, indicating a loss of 221, yet its overall headcount of athletes rose from 35.6% of campus to nearly half of the student body at 46.5% in 2021-22. In addition, BSC’s overall athletic expenditures also rose, up $412,506 from in the three-year period.

Anecdotally, these results suggest it is not athletes who are contributing to the downward trend of campus enrollment. And, therefore, it is not, perhaps, sports that can save a university on the brink of financial collapse. In fact, Josh Moody of Inside Higher Ed wrote in January 2023 that the year would be particularly hard on campus closures, citing declining enrollment and the cessation of funds COVID relief funds.

Moody quotes a senior policy analyst for the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association who sounded the alarm which appears to be ringing loudly.

“We think that there is going to be a catch-up of closures in 2023, and probably into 2024,” explained Rachel Burns. “It depends on how institutions have decided to spend down those federal funds, where they’ve invested them or given them directly to students. So it’s hard to predict when it’s going to happen and which type of institutions that it will happen to, but we anticipate a catching-up period to account for the past two years for colleges that would have closed but didn’t.”

None of this is to say that more universities will, in fact, close later this year and into next year. Nor is it to say that universities that continue to see their percentage of on-campus student-athletes grow will experience challenges.

University administrators at tuition-driven institutions wrestle with this reality each day: prospective student numbers are dropping while the cost of remaining competitive is increasing.

There is no magic formula to predict the next campus closure. Some campuses that closed were in rural settings while others were in urban centers. Some campuses were nearly 200 years old, while others were only around 50 years old.

Critiques on how American universities should deliver higher education to students originated more than a century ago with Abraham Flexner’s 1908 book, “The American College.” Also much discussed is the role of athletics in higher education. Excellent academic historical treaties have explored this (see, for example, “Sports & Freedom: The Rise of Big-Time College Athletics” or “The Game of Life: College Sports and Educational Values” and its sequel “Reclaiming the Game: College Sports and Educational Values”).

The common theme is the evolution of higher education. As John Thelin writes in the final paragraphs of his excellent book, “A History of American Higher Education,” “The resilience of American colleges and universities over the centuries, especially their capacity to add and absorb new constituencies, new institutions, and changing fields of teaching and research, endures as a remarkable heritage” (p. 361, 2004 edition).

Nearly 150 years removed from Walter Camp’s creation of college football, the importance of athletics on college campuses persists. The narrative for many campuses, however, appears to have evolved from how athletics contributes to educational values, past the “beer and circus” commercialization of college athletics, to the present-day, “can athletics save higher education?”

This newsletter is brought to you in part by Bold.org:

If you're a student in the US looking for a better way to pay for higher education, Bold provides thousands of students with $25k scholarships every year. Enter to win one of our monthly $25,000 scholarship to go towards your tuition, student loan debt, or other education related expenses!

If you’d like to buy ads on Extra Points OR in ADS3000, good news! They’re affordable, and we have openings this season. Drop me a line at [email protected]. If you have news tips, I’m at [email protected]. Otherwise, I’m at [email protected], @MattBrownEP on Twitter, @ExtraPointsMB on Instagram, and @MattBrown on Bluesky.