Good morning, and thanks for spending part of your day with Extra Points.

Friends, I’m excited to pass the mic over to a few Serious Professional Academics that suggested something I hadn’t really considered before…but think is worth your time.

That’s right. The idea that screaming cuss words at an Iowa football game because their offense sucks is your right as an American.

Neal C. Ternes, Ph.D., is an assistant professor of sport management within the Northern Illinois University department of kinesiology and physical education. His research focuses on public policy and sports with a particular interest in intercollegiate athletics and free speech at sporting events.

Monyae Williamson-Gourley, PhD, is an assistant professor of sport administration in the school of human services at the University of Cincinnati. Her research interests center diversity, equity and inclusion in sport.

Their remarks are below:

If you’ve been to a college sports event over the past few weeks, you might have noticed signs or videoboard announcements describing words and phrases you cannot say at the venue. Maybe you haven’t thought twice about it. After all, fans expect there to be rules of decorum most places they go, and given the spectrum of behaviors in the stands at college sporting events — from heckling to fights to throwing objects onto the field — it makes sense for facilities to have explicit rules about fan behavior.

At first glance, those rules can seem benign — but at most public college stadiums, the ways they are constructed is likely to be unconstitutional. For athletic departments, maintaining these policies risks future litigation from fans and even outside groups who believe these policies threaten their right to free expression.

There are broader philosophical concerns, as well. As academics, we are interested in how sports bring people together and foster community, particularly through the exchange of ideas. If you’ve been following national headlines the past few weeks, you might feel, as we do, that coming together now seems as important and challenging a task as ever. Political violence and censorship are threats to our core values as a country. Free speech is essential to the day-to-day work of public colleges and universities.

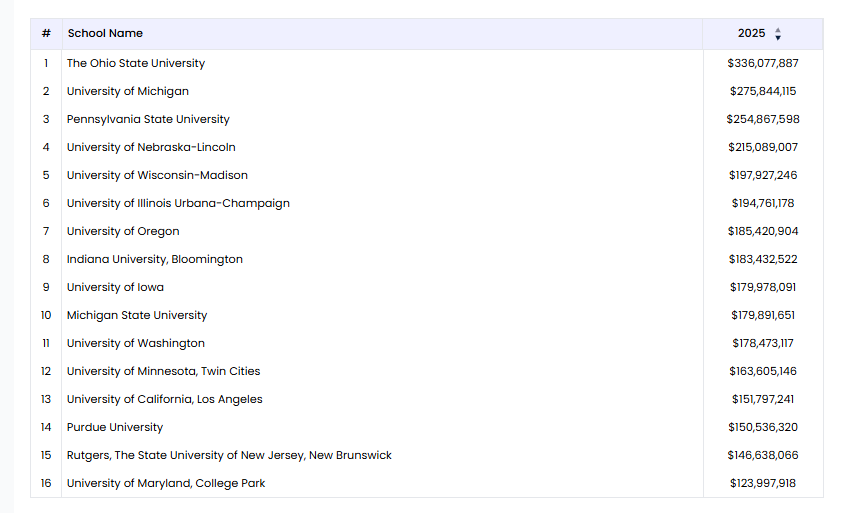

When our stadiums, some of the most visible symbols of our institutions, use unconstitutional speech codes, we undermine the values of our institutions and diminish the ability of our sports programs to foster community in the stands. And unfortunately, that’s happening across college sports. In our study of every FBS college athletic department’s posted stadium speech policies, we found that 92.2 percent of the public schools that posted restrictions on what fans can do, wear or say at sporting events had rules that violated First Amendment principles.

You’re probably wondering how more than 90 percent of public schools have stadium policies that violate federal law.

The answer? It’s not malicious. Athletic department officials are stretched thin to deal with all the moving parts that go into putting on college sports. In many cases, officials will copy and paste policies from other entities and call it a day, so one mistake can snowball quickly.

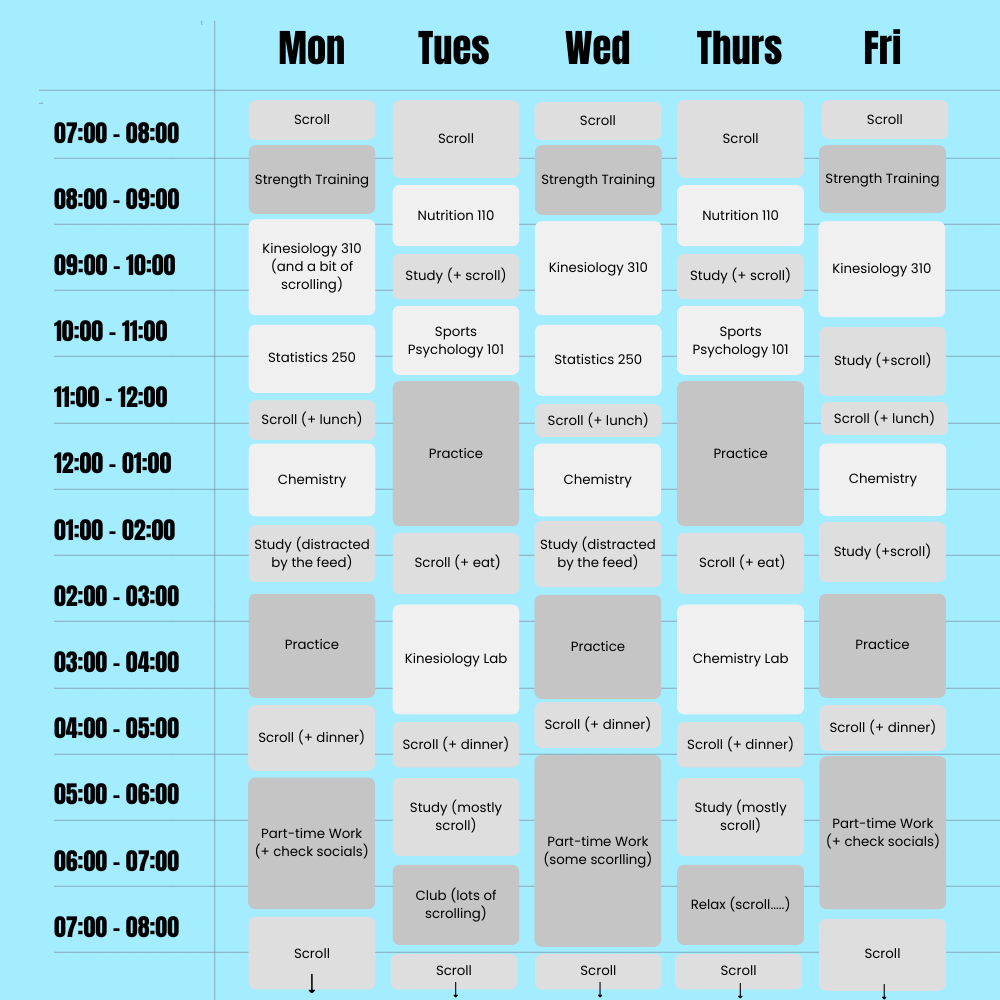

Is This Your Student-Athlete's Reality? Change It and Get 50% Off.

Fall semester means packed schedules: classes, practice, games, social time, and notifications competing for every spare moment. A science-backed 14-day program helps your student-athletes manage it all better.

Swipe Less, Live More helps athletes sleep better, stress less, and sharpen focus. Our 14-day program combines micro-lessons, daily challenges, and progress tracking with 95% finding the insights useful. Implementation is done-for-you and requires no additional staffing or overhead.

In partnership with Extra Points, the first 10 colleges get 50% off. Enroll as many student-athletes as you want: one team, first-years, or your entire department. Must implement by Thanksgiving. Only the first 10 schools get the deal. After that, the deal's gone.

Also, fans rarely litigate these policies, even when their implementation violates the First Amendment. Think about it: What fan wants to hire an attorney and sue an entity as powerful as a college athletic department over the fact that he was kicked out of a college football game because he was screaming obscenities about how terrible Iowa’s offense is? Even if someone stands by every word, the financial costs and possible reputational damage from suing are strong disincentives.

So why should school officials care?

First, because sports are the front porch of higher education, and they are how many people interact with colleges and universities. If state universities take a slapdash approach to speech rights in their sports facilities, why should visitors to those stadiums take officials seriously when they talk about the need for free speech elsewhere on campus?

Free speech is essential to the academic mission of universities, and as free speech on campus continues to receive intense political scrutiny, schools should make sure their policies reflect the values they purport to need in all areas of campus, not just when it is convenient.

Officials should also care because the current rules are so poorly written that they could be used to restrict speech based on political or religious messages that people historically do care about enough to file expensive lawsuits over. The exposure here is very real, and it’s unlikely that athletic department officials are keen on picking up even more legal bills right now.

Most of the policies we examined in our study were overbroad, a term used in First Amendment law to describe a policy that penalizes speech beyond what is intended. This can happen when the wording of a policy is unspecific about what type of speech it restricts and when its vagueness leaves interpretation in the hands of officials. Two great examples of this come from Ohio State and Florida State.

Ohio State’s fan conduct policy includes a section that reads: “Guests should wear clothing without obscene or indecent messages. Guests will remove or cover up such clothing deemed offensive or obscene upon request.” First, the word “obscene” has a specific meaning in First Amendment law that is generally limited to highly disturbing sexual content like child pornography. Ohio State and many other universities are more likely using the term as a synonym for “offensive,” which is both repetitive and a problem; public entities cannot enact bans on speech based on whatever they decide is offensive.

If they could, one might, for example, argue that the Michigan logo is offensive and shouldn’t be worn in Ohio Stadium. To quote the Supreme Court majority in Cohen v. California, a landmark political speech case: “One man’s vulgarity is another’s lyric.” That case involved a man wearing a jacket that read “Fuck the Draft” inside a state courthouse. Why would a “Fuck Michigan” shirt at Ohio Stadium (or at Michigan Stadium, for that matter) be any less protected?

The bigger problem is that blanket bans on offensive speech give stadium officials an unconstitutional amount of power to decide what messages are permissible inside a public space.

What if someone were to decide that clothing that said “Trump was right about everything” or “trans women are women too” were offensive? If someone in the stands were to sit down during the national anthem or start a “Let’s go Brandon” chant, would they be escorted out because their speech is offensive?

These examples probably seem ridiculous, but that is the point. The policies that an overwhelming majority of FBS institutions are using are so poorly crafted that they give stadium officials a ridiculous amount of authority over speech in public spaces.

Several schools have attempted to limit speech by prohibiting political messages, which also doesn’t work. College sports are inherently tied to politics in so many ways that restrictions on political speech are, if implemented, merely restrictions on political speech that stadium operators don’t like. How is an Iowa State fan supposed to follow the university’s ban on political messages at Hilton Coliseum when Gov. Kim Reynolds shows up to a game (as she often does) and is shown on the videoboard? Both cheers and boos for her send a political message, so it would seem the only way to follow the policy would be for fans to ignore the governor entirely.

That gets us to the biggest problem: Overbreadth doctrine allows people to sue because they anticipate that they might be negatively affected by a policy, even if they haven’t tested the enforcement of that policy on their speech.

Overbroad regulations create a chilling effect, meaning people may limit their speech out of fear that what they do or say could be punished. These are particularly relevant for stadiums with policies specifically targeting clothing or signs, as fans may worry that they won’t even be allowed inside the venue. Courts allow regulations to be challenged as overbroad precisely to avoid this uncertainty, so someone wouldn’t need to wait until an official at Ohio Stadium stops him from wearing a keffiyeh or holding up a sign that says “I stand with Israel” at a game to file a lawsuit.

Let’s be very clear: We are not saying it’s your constitutional right to throw mustard bottles on the field at your next football game. (Sorry, Tennessee fans.) Behavior that is otherwise illegal — like public intoxication, throwing objects onto the field or fighting — is still illegal. Nor are we unsympathetic to the need to curb behavior that is discriminatory or makes anyone feel unwelcome or unsafe. College sports can and should be for everyone, but that doesn’t happen through vague policies that unconstitutionally limit speech.

Athletic departments don’t need to abandon their fan codes of conduct; they just need to improve them by making them more focused. They can start by removing generalized language that prohibits speech that is offensive or because it belongs to a specific category of non-commercial speech. If schools are worried about fans bringing in offensive signs, ban signs entirely or limit their size rather than trying to restrict their content. Schools should focus on promoting good behavior rather than punishing undesirable but still legal behavior.

These solutions are not comprehensive, and we are pursuing more research into techniques schools can use to create better game environments without violating fans’ free speech. Still, schools need to start making changes so that they can better embody the free speech values they espouse and so that they are not risking even more costly litigation in the future.