Good morning, and thanks for spending part of your day with Extra Points.

Real quick, before I get to the story today, I want to let you all know about a tweak I’ve made to the Extra Points Referral Program.

At the bottom of just about every newsletter, you’ll see a unique referral code. I know that many of you already share Extra Points on Reddit, Twitter, and various message boards, as well as with colleagues across the industry. This is a major way that the newsletter grows, and I want to encourage it!

I’ve adjusted a few of the referral rewards to make them easier. Now, you can get a free month of Extra Points by referring just two readers. I've also made it easier to get our free bonus content (cutting room material from my book + updates on my next one), annual subscriptions, and other rewards, like a $100 gift card to Homefield Apparel.

You can use the box below to get your referral code and start earning rewards.

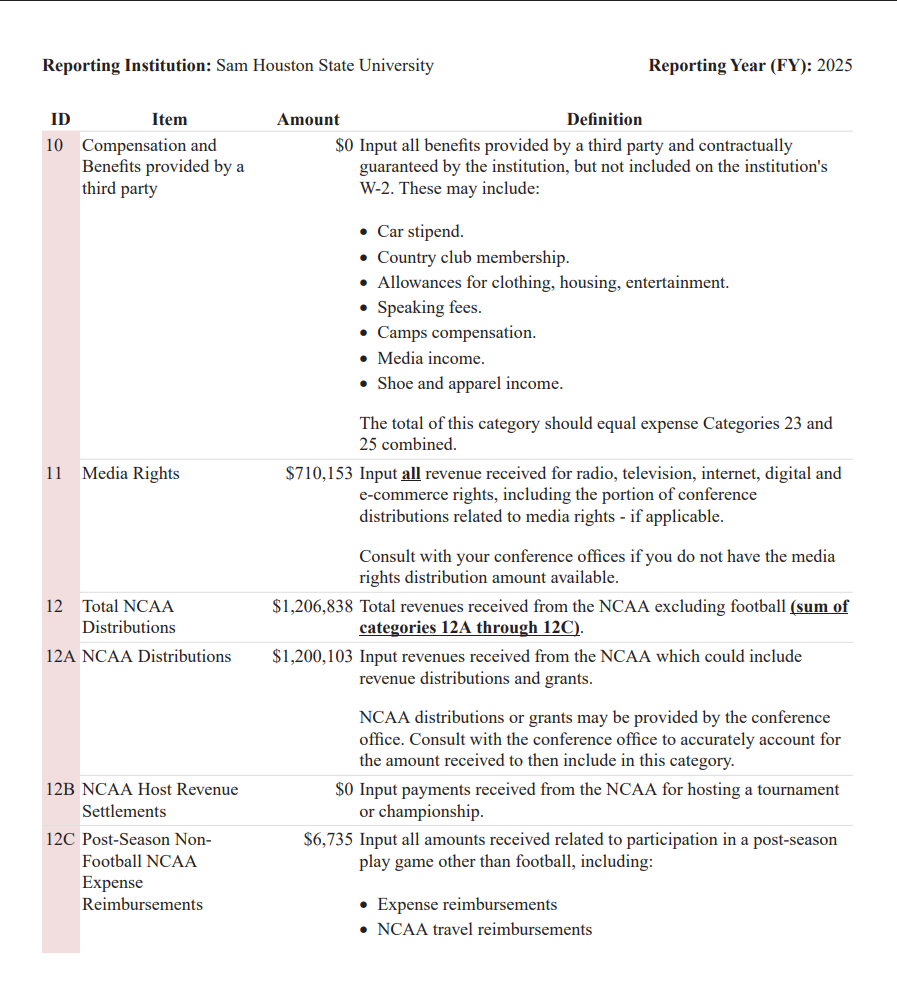

Every college athletic department is different, but most of them earn revenue in similar ways. Beyond ticket sales, NCAA revenue distributions, and student fees, schools earn money from a variety of contracts. They’ll earn money from broadcast revenue, ranging from tens of millions of dollars to less than the cost of production. They’ll earn money from pouring rights (Coke or Pepsi?) and potentially earn money from athletic apparel deals (even though most schools are just getting product).

For many schools, the contract that actually pays them the most is their multimedia rights deal, or MMR.

What is MMR?

Multimedia rights aren’t broadcast rights and don’t typically have anything to do with broadcasting sporting events. It’s a catchall term for an athletic department's sponsorship and advertising rights. That includes everything from radio rights to the signage around arena scoreboards, to licensing revenue, athletic department websites, and more.

Even for low-major schools, that represents a lot of potential inventory, in a variety of different categories. While many schools sell this inventory themselves, the majority of D-I schools work with third-party companies to help package and sell this stuff. You might have heard of some of these companies…JMI, Van Wagner, Playfly, and the largest, Learfield.

If a school decides to work with a thirty party for MMR sales, the contracts typically are structured in one of two ways. A school might elect to set up a revenue share with the MMR company (school gets X% of revenue up to Y point, then Z% of revenue beyond that, etc), or some sort of guaranteed revenue (school gets $800,000 a year for X years). Usually, a school can make more money from a revenue split, but many schools elected to take a guarantee, since that’s easier to budget for longterm, and helps mitigate potential uncertainty.

For a P5 school, the guarantee from an MMR contract is typically well north of $5 million a year. G5s and non-football mid-majors will occasionally have seven-figure guarantees, but healthy six-figure contracts are more common.

But that model may be changing

I’ve heard variations of this story from MMR executives, sales consultants, and athletic directors over the last two years. The MMR world is very competitive, and in an effort to ensure they had a dominant market share, Learfield may have agreed to some contracts that were overly generous, not unlike what happened with Under Armour overpaying to break into new college markets in the 2010s.

Every school deal also helped add new inventory for national sales packages for other deals, and also took inventory off the board for rivals, so it could have been completely defensible to sign a deal that lost a few hundred thousand dollars at say, a New Mexico or Utah State, so long as the company had profitable deals elsewhere.

But then a few things changed. In 2018, Learfield merged with IMG College after a long investigation by the Justice Department over whether such a conglomerate would have monopoly power. And then in 2020, COVID blew a hole in every facet of the college sports business.

Post-merger, Learfield became a massive company that could touch virtually every component of the college athletics industry. But it now also had an awful lot of debt, increased investor pressures, and some less-profitable contracts on the balance sheet.

Even as far back as 2020, Learfield was reportedly trying to renegotiate many of these deals, shifting from guarantees to revenue-sharing models. Industry sources have told me that while Learfield wasn’t the only vendor to have conversations with schools about contract restructuring during a global pandemic, many ADs felt that the company was trying to use the event to “clear some salary cap room”, so to speak, by shifting risk from the MMR firm back to the campuses over a longer period of time.

While many P5 schools tweaked their deals around 2020, industry experts have told me that the absolute biggest brands in the sport mostly avoided significant, long-term contract adjustments that they didn’t want.

But now, it appears that nobody is immune

Last week, Sportico reported that Learfield had engaged with six different big-time schools, including UCLA and Florida State, to restructure their MMR deals. Learfield works with most of the largest brands in college sports, including programs like Alabama, Michigan, Ohio State, and Texas.

Per Sportico, all six of the deals were signed before the 2018 merger with IMG.

Debt management now appears to be a major challenge for Learfield. Back in January, Learfield and the company’s creditors reached out to restructuring attorneys.

Per Sportico:

Learfield’s debt maturities include a total of $58 million in payments due May 31, June 30 and July 31, and a bigger chunk due Sept. 1, according to S&P. The college fiscal year ends June 30, and many of Learfield’s contracts, perSportico’s review of more than three dozen obtained via public records requests, include at least partial payments owed at fiscal year’s end. Two of the company’s other outstanding loans, which amount to $970 million, are due Dec. 1. Another $75 million is due in December 2024.

S&P predicted in January that the company “will not be able to repay all its debts coming due this year,” and downgraded Learfield’s credit rating further into junk territory.

That’s a lot of money.

In the story, Learfield CEO Cole Gahagan told Sportico that those six contracts were “legacy deals that yielded significant losses” and that no additional renegotiations are planned.”

This is potentially a big story for reasons that have nothing to do with Learfield…or even MMR

But first, a lot of schools work with Learfield right now. If you are a fan and you root for a P5 program or a mid-major that a lot of people have heard of, your school probably works with Learfield in some capacity. If the company can go back and force a UCLA or a Florida State to accept less money or change the terms of their contract, chances are, they could do it for your school.

As I’ve talked to ADs and industry consultants over the last few weeks, even before this Sportico story was published, I’ve heard reoccurring concerns over exactly how ironclad any longterm contract is these days. Many of Under Armour’s apparel contracts were longterm…until they weren’t. The ACC’s Grant of Rights appears to be secure right now, but lawyers are going to keep picking at it, and eventually, it could be challenged.

The concern that I have been hearing isn’t about Learfield being some terrible company, or that their competitors are better…but rather, '“How can we, the school, protect ourselves in case something changes with our key partners?”

That might mean trying to do more business operations in-house. That requires additional hiring and up-front money, but very small and very large schools have been able to successfully do their own MMR sales, or their own ticket sales. But there are limitations to that philosophy…no D-I school is proposing to make their own shoes, cook all their own concessions, or broadcast all of their own games.

Trying to run a college athletic department in 2023 is an exercise in managing risk and uncertainties. Higher education is changing, the national advertising market is changing, the TV delivery model is changing, and the legal and regulatory framework of college sports is changing, potentially very quickly and very significantly. You still need to raise money, sell tickets and make payroll…but everybody is out here making forecasts in a world with massive unknowns.

If you’re a fan, don’t be surprised if your alma mater calls you up, asking for more money because some vendor contracts had to be rewritten and the department is out $800,000 they thought they’d have for next fiscal year.

And if you work in the industry, well, call your lawyers. Again. Just in case.

This newsletter is brought to you in part by Collectors.Wiki:

Take your skills to the next level...Get access to a huge DIY woodworking plans collection!

Our carefully curated collection includes projects suitable for both beginners and advanced woodworkers. Each plan comes with crystal-clear step-by-step instructions and detailed blueprints to guide you along the way. But that's not all. As a subscriber, you'll also gain access to a treasure trove of essential tricks and guides to improve your workshop, tools, and project outcomes. Our team of expert woodworkers has put together a comprehensive collection of resources that will help you unlock your inner craftsman. And the best part? You can get access to all of this for free!

→ Get Free Access here:

To sponsor a future Extra Points newsletter, please email [email protected]. For article ideas, newsletter feedback, FOIA tips, athlete NIL sponsorships and more, I'm at [email protected], or @MattBrownEP on Twitter, and @ExtraPointsMB on Instagram.