Good morning!

I reckon I’ve got about two more spots for mailbag questions, so if you have a question about college football history, or an off-the-field sort of topic that gets covered by Extra Points, shoot me a tweet at @MattSBN, or an email at [email protected].

Schools are spending lots of money on football recruiting. Let’s try to understand those numbers a little better.

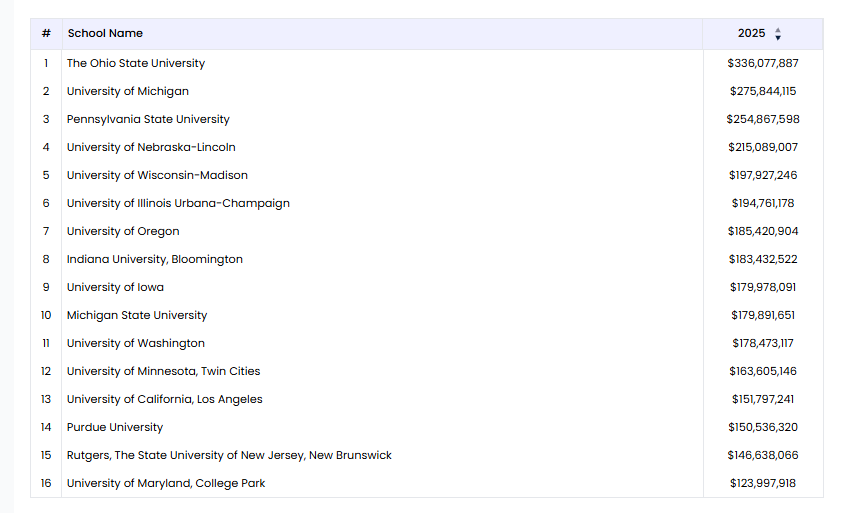

Earlier this month, I shared a story from Stadium that took a look at how much schools tell the NCAA they spend on recruiting. It’s interesting data, and while it followed a general trend that you’d probably expect, i.e. teams that usually sign the best recruiting classes spent the most money and teams in the SEC usually spent more than other schools, it certainly wasn’t a linear relationship.

Stadium published a few itemized budgets for the biggest spenders like Oregon and LSU. I was curious what the breakdown might look like for some of the more frugal institutions. Texas Tech actually sent me a report so detailed I could tell you exactly where the school bought food for recruits. Here’s a snippet of what that looks like:

While LSU reported spending well over $100,000 on food for recruiting, schools like Kansas State ($62,350) and East Carolina (~$56,000) spent much less (data provided to me via Open Records requests).

I wanted to know how this could happen, so I reached out to multiple people who work in recruiting operations, from big budget P5 type programs to AAC institutions. Here’s what they told me about how food is calculated, how these budgets work, and what we can learn from them.

1) My first thought was, “well, LSU is probably bringing in just the most expensive restaurant in Baton Rouge for official visits.” I was told this probably isn’t the case because most schools are hosting kids on official and unofficial visits at the same time, and the kids on unofficials are supposed to pay for their share of the food. So if you decide to bring in like, grilled panda or something (which hey, anything is possible with LSU), you’re going to make the visit prohibitively expensive for unofficials. In an ideal world, you want a kid on your campus as much as possible. If you’re sticking them with a $60 dinner, coupled with other expenses they need to shoulder, they may only come once. That could put you at a disadvantage.

A school isn’t going to bring in Taco Bell for a huge gaggle of visiting recruits (even if, let’s be honest, a lot of them would probably like that), but they’re not bringing out the Endangered Species Platter either.

2) It’s also unlikely that one school is feeding hundreds more kids than another. The number of official visits a school can host is capped, so while there may be variance dependent on roster room, it shouldn’t be enough to explain massive spending differences alone. And while unofficial visits are uncapped, again, the kids are supposed to pay those costs.

3) I was told there are two big factors at play for looking at what schools spend on food. One is kickoff time. A school that has lots of kickoffs at noon isn’t going to spring for quite as elaborate of a spread (think brunch) as a night game, that might go for a bigger dinner.

4) The single biggest recruiting department expense, I’m told, is usually travel. I was told this is especially difficult for schools to budget and plan for. After all, you’re not entirely sure where you might have to travel (or how often) to lock down a recruiting class, and since teenagers are notoriously flakey, schools have to be highly flexible with their travel plans, even if that costs extra money. The amount that different schools have to travel also varies a lot. Miami could sign a really good recruiting class without signing a kid north of Tampa. Wyoming might not sign a kid within 300 miles of campus. So many, tiny variables impact what a travel spend might look like and how it is reflected in the official budget.

5) The other, and this is key when looking at athletic budgets generally, is accounting differences. Sure, just about everybody is going to count the money they spent on the actual food as “food, recruiting” in the expense book. But what about the tables, chairs and tents? Do you own those, or did you subcontract them? What about the insurance? Was any food prepared on site?

What was stressed to me is that different schools may categorize different aspects of the hosting process as operations, or salaries under a different department, which will show up differently on a budget. A school with a smaller recruiting department that has to spend more on outside vendors might also show an artificially high recruiting spend number. Making a true apples-to-apples comparison is almost impossible without itemized budgets.

For example, here’s UGA athletic director Greg McGarity, discussing how travel expenses are recorded:

Yet in a previous job, McGarity oversaw aviation for the University of Florida's athletic department, which he said had access to two private planes.

“That was a great thing to be able to use the aircraft at Florida because their budgets just had to absorb the fuel costs,” McGarity said. “The pilots were on salary. The plane, it was all in a different account. It’s different than us. Basically, we just write a check to a vendor for the trip, whichever trip that our coaches may be on.

Two different big-budget schools doing big-budget things, but could have their recruiting expenses tabulated (and reported) in a completely different way.

Or here’s Florida State’s new athletic director:

Coburn was appointed FSU's athletic director in May after serving since August 2018 in an interim role, and he has spent much of his time in chargeaddressing an athletics department budget deficit, which has necessitated cuts.

During the 2018 fiscal year, FSU's recruiting costs for football dropped back to $1.58 million while Seminoles head football coach Jimbo Fisher departed in December 2017 for Texas A&M.

Coburn said the dramatic jump in recruiting costs in 2017 could have been because of changes in the accounting process. He added, "I suspect that there may have been more use of private planes that one particular year," but with sweeping changes since atop FSU's department and football program, Coburn said he couldn't "really find anyone who can give me a good explanation for that jump."

If the guy in charge of the dang athletic department can’t entirely divine meaning from the budget, how the hell is anybody else supposed to? This seems…not entirely healthy!

Are there any actual takeaways from this, besides ‘gee wiz math is hard, I shouldn’t have gotten a degree in political science’?

I think the general takeaway from USA TODAY’s hit, that recruiting costs are growing significantly, is almost certainly true, no matter how that money is spun by the accounting department. If you had to spend $500,000 on something to improve your football team, spending it on talent acquisition will likely have a better ROI than a facility remodel or WiFi at the stadium. It might even be better than $500,000 spent on a coach.

Generally speaking, even though there are lots of other variables to consider, like geography, conference affiliation, program history, admission standards and more, spending more money on recruiting helps land better recruits.

A cynic might look at all of this spending to attract very good college football players as proof that very good college football players have some sort of financial value, perhaps one even greater than that of a college scholarship, and ought to be compensated as such. Perhaps this will be discussed in the next NCAA Special Working Group Council Committee To Stop Jay Bilas From Sending Mean Tweets About Us.

It’s a small thing in the grand scope of trying to reform college athletics, but I think it would be nice if college athletic department financial reporting was more standardized and centralized, so the public could evaluate and understand it. Most of these schools are public schools, after all. Even if the money they’re spending is donor money, and not taxpayer or student-fee money (at least not directly), I think the public has a right to have a better idea with how exactly schools are spending and investing it, especially as debates over amateurism and what schools could “afford” rage on.

Who knows if these boom times can go on forever. But they’re going on now. And no matter how you parse or slice through the data, it sure looks like a good time to be in the “sell stuff to schools to help them recruit” business.

Thanks for reading and supporting Extra Points. If you are enjoying what you read, tell some friends. If you have questions, comments, budget documents you’d love to leak, an accounting class you’d like to teach me, or mailbag questions, hit me up at @MattSBN, or [email protected].