Good morning, and thank you for spending part of your day with Extra Points. If you found this newsletter from Twitter, or a message board, or somewhere else, I can email these newsletters directly to you! For free! You just have to hit this button right here.

I’ve probably written and deleted a good 1,000 words debunking the crazy Ohio State fan conspiracy theory that “ESPN hates their team” half a dozen times tonight, before finally realizing that…do I really want to keep having that conversation in my timeline for the next week? No, probably not. I’m not sure I have the stomach to hammer out Manufacturing Consent, but for college football, or why the existence of Mark May does not a corporate conspiracy make. Maybe later.

Instead, I want to take a closer look at this story from Forbes, that I think puts an important twist on the idea of college athlete likenesses having important commercial value. We’ve been talking a lot about their value as advertising entities, spokespeople, etc. But what about their…biological data?

Now that California and a host of other states have proposed legislation to undo this, there is one other discussion point that athletes at all levels should seek to own and control—their biometric data.

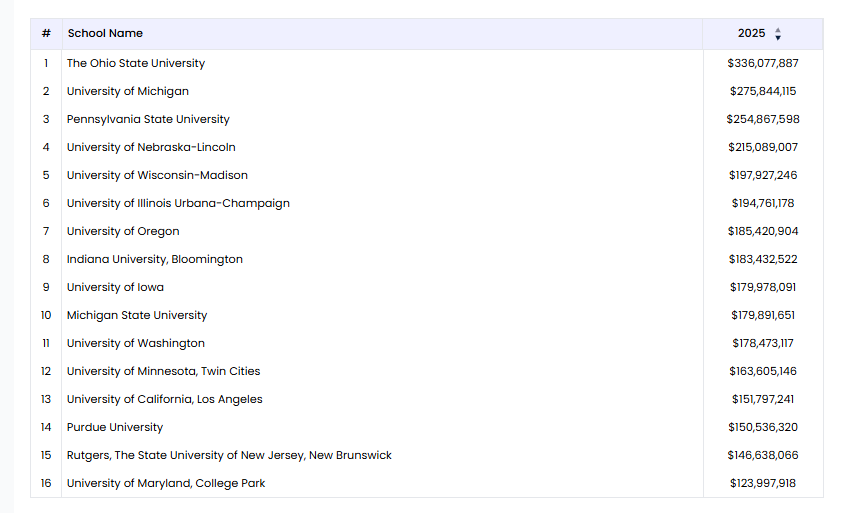

The University of Michigan was the first major college brand to consent to collecting private performance data from their athletes as part of their apparel contract. The Wolverines signed with Jumpman, Nike’s Michael Jordan branded apparel division. As part of that agreement, the $170 million deal may “allow Nike to harvest personal data from Michigan athletes through the use of wearable technology like heart-rate monitors, GPS trackers and other devices that log myriad biological activities”, according to a story in the New York Times.

…

For starters, consider the well-known Polar pro chest straps, heavily used at practices. Data is collected on exertion rates at certain points in practice or competition. After that data is reviewed by the player and the coach, what happens to it? Who owns it? How will it be used going forward?

This is a really good question that I hadn’t considered at all, especially in light of more universities turning to apps to track students, generally, like SpotterEdu.

Trying to maintain some sense of digital privacy in almost hilariously quaint, but regular ol’ consumers have some choices in how they engage with services that might harvest their data. You don’t have to use Facebook, or at least, most of us don’t. You don’t have to buy a Google assistant. You can take some personal privacy protections with your network setup.

But could a Michigan football player decline to use any of the Nike gear that may harvest their biometric data? Are players realistically informed of what may happen with their biometric data? Does the athletic department even know?

After publication of this newsletter, Extra Points reader Bill Wilson shared a post he wrote after this contract was announced that makes it pretty clear that the athletic department, or at least the members of the athletic department that wrote the contract, very much understands the value of this data.

More important, though, are the brand-new provisions which pertain to the right to player-generated data. An entirely new definitional category is described on page one, labelled, “Activity-Based-Information,” which is defined as “performance and/or activity information/data digitally collected from the Teams or Team members during competition, training or other cover Program Activities, including but not limited to speed, distance, vertical leap height, maximum time aloft, shot attempts, ball possession, heart rate, running route, etc.

”The operative lawyer’s term here is ‘including, but not limited to,’ which means that this is a nice, innocuous-appearing list, but it’s tiny compared to the tractor-trailer load of data which Nike can haul off with, as a result of this provision.

And Michigan grants to Nike the “right to utilize . . . Activity Based Information . . . in all media including, but not limited to, the worldwide web and other interactive and multimedia technologies, in connection with the manufacture, advertising, marketing, promotion and sale of Nike products and Digital Features and programming [which use shall be] on an aggregated, anonymous and de-identified basis and otherwise in compliance with [Big Ten, NCAA, and Michigan] regulations.”

…

In this era of the explosion of publicity and promotional rights, and of the personal brand, Michigan has just signed a ten-year contract ceding to Nike personal player performance data. Even though the data is “de-identified’ it has, in the aggregate, tremendous, if not fabulous potential value: obviously, Nike intends to aggregate that data, on an ongoing basis, by inserting these ‘right to Activity-Based-Information’ provisions in contracts with every school — and Nike intends to then sell aggregated performance data, as a product, for increasingly large amounts.

Maybe the risk of individual harm should this particular data get out, at this current time, is relatively low for a college athlete, although I could imagine scenarios where it could be shared with NFL personnel in a way that an athlete wouldn’t want. Perhaps more damaging, or at least embarrassing, personal information about them floating around the internet or in some corporate data center than their practice GPS data. But that’s still their data! In a professional league, what happens to that information sounds like something that would be collectively bargained over. But since athletes are not employees and do not have a union, they don’t have the ability to do that.

As this debate evolves over 2020, and probably enters the court system, it would be nice if somebody…federal lawmakers, student advocates, somebody else, pushed for athletes to have more control over their own performance and biological data, especially if it has commercial value to a university partner.

This is just the latest example that proves that athletes have valuable commercial potential

I was doing a little re-reading over the holidays, and was struck by this story that makes it crystal clear that college athletes, particularly big time players at big time programs, had commercial value.

This is from John Watterson’s College Football: History, Spectacle, Controversy, on former Yale captain James Hogan:

Though from a poor family, Hogan lived in the finest dormitory. He also took a free trip to Cuba with the Yale trainer, Mike Murphy, and was given the lucrative franchise of representing the American Tobacco Company on campus. According to an official of the company, the player talked up the cigarettes to his friends. “They appreciate and like him; they realize that he is a poor fellow, working his way through college and they want to help him,” a company official declared. “So they buy our cigarettes, knowing that Hogan gets a commission on every box sold in New Haven.” Asked if other Yale students had this opportunity, the official responded that they do not — Hogan’s job was simply an experiment.

This was in the early 1900s!The American Tobacco Company wasn’t a charity, or a booster organization for Yale. It was in the business of selling cigarettes, and commissioning a popular football player as the sales representative would have been good business. The player got money (which Hogan badly needed, seeing as he enrolled in prep school at 23 and didn’t enroll at Yale until he was 27), and so did the American Tobacco Company.

Hogan was also alleged to have a deal allowing him to keep the profits from selling scorecards at Yale baseball games. Another top recruit, a lineman named James Cooney, had a similar arrangement at Princeton, according to Watterson’s book.

This was true because college football has almost always been a big business

Concerns over spending in college athletics seem to pop up even more during bowl season, when the ridiculousness of the whole enterprise is even more brazen. But while the sheer economic scale of college football has skyrocketed in the deregulated TV era, the idea that this sport was a huge business, and thus would attract the interest of other businesses, is almost as old as the sport itself. When a lot of people care about something, it becomes a big business.

Take Harvard, for example. In Henry Beach Needham’s exposé on recruiting practices in McClure’s Magazine in 1905, he wrote that Harvard football took in $72,569.81 in ticket sales for the 1904 season. Adjusted for inflation, that’s over $2 million, which is about what a MAC school might make in 2019. Yale’s athletic department took in $106,393 in total revenues, most of which came from football ticket sales in 1904, which would be about $3 million today.

Concerns about the dangers of big money in college football were so great that one of the major issues Western Conference (now known as the Big Ten) administrators tried to address in meetings around the turn of the century was price-gouging on tickets.

They wanted to fix ticket prices to 50 cents, per Winton Solberg’s Creating The Big Ten, Courage, Corruption and Commercialization. Tickets for Michigan or Chicago games could easily go for $2 or $3, or about $84 in today’s money. That’s about what a ticket to a big game might cost now.

I have an interview with a college athletics administrator on the rising costs of the sport that I hope to share soon, and I imagine it will continue to be a talking point over the next few months. And I’ll continue to try and wrap my arms around the massive likeness rights debates, committees, legal challenges and more. It certainly seems like we’re going to get more federal government involvement.

However it shakes out, I hope the solution includes all the ways an athlete has value, from their likeness, to their biometric data, to whatever else comes up.

The specific industries change, and some of the supporting detailed have changed, but the central arguments here in college football….probably haven’t changed that much

Well, except for that whole Yale being good at football thing.

Thanks again for supporting Extra Points, which publishes at least twice a week on the off the field issues that impact what you see on the field in college football. Mailbag questions, hot tips, feedback and more can be sent to [email protected], or to @MattBrownEP on Twitter. And if you enjoyed this newsletter, or other Extra Points newsletters, please share them with pals on the internet.