College athletics is a big business. In fact, it’s probably never been a bigger business.

But college athletics is also not a business.

Confused? I don’t blame you. But stick with me for a second.

The point of a business, be that McDonald's, Nationwide Insurance, or the Utah Jazz, is to generate a profit. All that money left over from paying salaries and expenses? Sure, you can reinvest some of that, but it can also be pocketed as profit for the owners and investors.

You can’t really do that in college sports. There’s no owner. The athletic departments themselves are configured as non-profits, and if they want to keep that tax exemption, they have to at least pretend like that's what they are. Nobody is trying to make a profit, there are no investors to pay. The “profit” is in winning championships and keeping donors happy.

So that leads to a weird, hybrid industry. On one hand, college athletics is very much a mature industry, one that can generate hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue from broadcast rights, ticket sales and licensing fees. Athletic departments make key strategic decisions with revenue in mind, and they heavily compete against each other.

But on the other hand, it’s also tied to higher education. They don’t pay salaries to any of the athletes (at least, not yet), they have to run dozens of other athletic programs that may not have commercial appeal, and much of the legal and regulatory environment that supports and defines other businesses only sort of applies to college sports.

So that makes this world difficult to understand. Throw in legal challenges coming from antitrust, Title IX and labor classification, the House settlement that will finally allow schools to pay athletes directly, the transfer portal, NIL, conference realignment and everything else…and even the people who work in this industry are confused.

That’s where I come in.

Extra Points is here to cover the off-the-field stuff that shapes college athletics, from the Ohio States to the Ohio Dominicans. Four days a week, I’m writing about public policy, TV deals, NCAA administrative changes, and much more.

But before we get to all of that, we want to start with the basics. Here, I’ve written out a brief overview on how athletic departments earn (and spend) money, how NIL (real and fake) works right now, how shoe contracts work, and a few other major college sports topics:

Trying to explain everything in the depth it deserves doesn’t make sense here. That would be a book. Maybe I’ll get around to writing it some day.

But today, you can enjoy the Cliff Notes. I hope this helps clarify some of how this crazy industry works, and helps you become a more informed fan. And if you enjoy it, I bet you’ll love Extra Points.

Thanks for reading. I hope to see you around the internet.

-Matt Brown

Founder and Publisher

Extra Points

Where does the money come from?

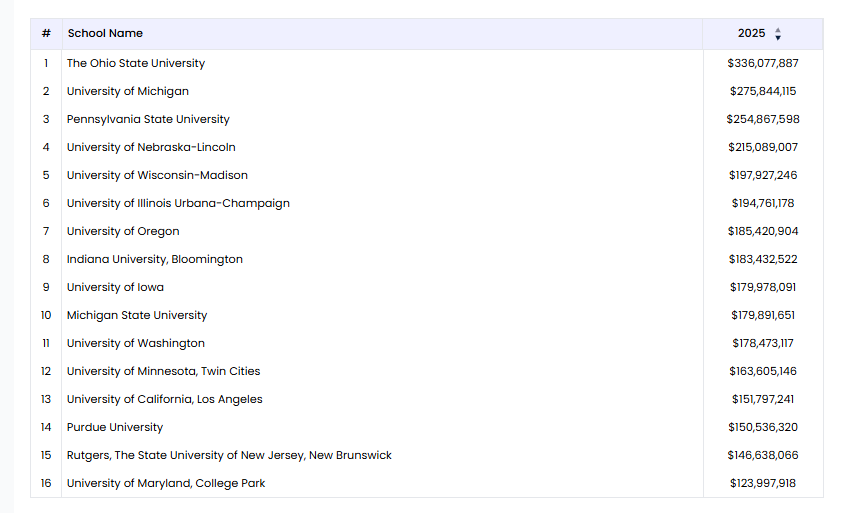

Athletic department budgets are very different. The largest departments, schools like Ohio State, Texas and Michigan, will regularly generate north of $200 million a year in revenue. The FBS median revenue figure is around $88 million, but many small schools in the NEC, Southland, MEAC or SWAC may generate under $20 million. While all D-I athletic departments sell tickets, charge for parking and get money for having their games on TV, how they actually fund their departments varies very significantly.

For the largest athletic departments, typically institutions in power conferences like the Big Ten or SEC, the single biggest revenue driver each year comes from conference media rights. In 2022, the Big Ten signed a seven-year contract with Fox, CBS and NBC that is worth more than $7 billion dollars. By the end of that contract, Big Ten institutions will earn more than $70 million a year in TV rights alone, with SEC schools right behind them. Institutions in the Big 12 and ACC will earn more than $40 million a year near the back half of the decade.

But that TV money doesn’t necessarily trickle down to everybody else. The Mountain West Conference, home of College Football Playoff participant Boise State, paid out roughly $5 million per school in FY23. TV distributions for Conference USA and MAC programs are less than a million dollars per year, and schools at the bottom of D-I might not make anything. ESPN still pays a rights fee to put OVC games on TV, but the conference may elect to use that money to buy linear TV slots, or to help defray production costs that the schools have to pick up. Nobody is making big time TV money in a single-bid college basketball conference.

After TV money, ticket sales are often the second-largest source of athletic department revenue. Everybody sells tickets, but when your football stadium fits over 100,000 fans, like it does at Michigan, Penn State or Tennessee, you’re likely to make juuuuust a bit more money than Middle Tennessee State or Fordham. Texas led the country in FY24 in generating more than $60 million ticket sales…money that came not just from football, but baseball, basketball, volleyball, and other sports. Seven schools generated more than $50 million.

Football, as you’d probably guess, is overwhelmingly the largest source of ticket revenue, but departments that earn more than $40 million a year in tickets almost always have other sports that put a lot of butts in seats. Basketball is usually number two, but a handful of programs bring in seven figures in hockey, baseball, gymnastics, and other sports.

There are a few other ways that larger programs are able to bring in revenue. Schools can earn NCAA “units” for successful performances in the Men’s and Women’s NCAA basketball tournament, payments that can extend into six and seven figures. Athletic departments ask for donor gifts, either in cash or corporate in-kind partnerships. Schools can also rent out their athletic facilities to other organizations (like high schools), sell parking spaces, hot dogs and programs, hold sports camps, and license their intellectual property for stuff like t-shirts or video games.

While basically every school at least tries to raise funds from donors or chase licensing revenue, it is very hard for smaller athletic departments to earn meaningful revenue in the same ways. So smaller schools have two other tools at their disposal that are mostly not employed by larger programs.

One is the game guarantee. Ever notice that Kent State plays two or three big-name programs to start every season in football? Or that some small college basketball programs basically play their first month on the road? Big schools that want a larger number of home games will pay a “game guarantee” to a smaller school who is willing to hit the road and be a body bag for a bit. A college basketball team might earn anywhere from $65,000 to $120,000 for taking a guarantee game, while a football team can earn close to $2 million. An athletic department can make north of $5 million a year just by allowing themselves to get knocked around by Ohio State or Notre Dame a few times. And hey, every year, a few of those teams collect the paycheck and grab the W.

The other lever is from the university itself. Student fees are very common across mid and low-majors, although even a few big-time programs utilize them. A student fee is a charge applied to every student, whether they go to any college athletic events or not. They can range anywhere from $75 a semester, to $800, to even more. We can debate the wisdom of these student fees, but for mid-majors, you can’t deny their importance in keeping the lights on.

Beyond student fees, athletic departments can also just accept funding from the university itself. Sometimes this has nothing to do with cash, (a cafeteria that feeds athletes might be organized under a different department and count as a university subsidy, for example), but sometimes that’s exactly what it is…central campus handing over a check to cover athletic department operations.

A few dozen of the largest athletic brands each year report that they are financially self-sufficient. Another few dozen could be, if they had accounting incentives to do so. But for the bulk of college sports, the athletic departments don’t generate anywhere close to enough ticket, concessions, or donation revenue to pay expenses. They have to rely on the school and the students to keep the lights on.

This, from the Knight Newhouse Athletic Database, charts how revenue is earned from D1 schools without football in FY23. Think schools like Northern Kentucky, UT-Arlington, Pepperdine, etc. This breakdown is pretty common, in my professional experience:

Compare that to say, the Big Ten:

Those are two very, very different distributions.

Where does the money go?

A lot of different places!

Typically, the single biggest expense item centers around facilities and equipment. Sure, most people know it's expensive to build stadiums, but it’s also expensive to maintain them. New field turf, electrical and heating bills, insurance, and debt service can easily add up to eight figures or more a year for a larger athletic department.

Then, you’ve got salaries. In financial reports to the NCAA, schools are required to break up their salary spending on coaches and non-coaches. Non-coaches may include the athletic director and senior level athletic department staff, but also folks like athletic trainers, team psychologists, academic support staff, operations staff, graphic designers, marketers, and many others.

Compensation for these roles can vary wildly. At the highest level, head football coaches can easily earn more than $8 million a year, coordinators more than $2 million a year, position coaches close to a million a year, and elite basketball coaches bring in more than $4 million. A P4 athletic director is likely to earn between $1.5-$3 million a year. At the bottom end, many head coaches of Olympic sports beyond the P4 don’t even make full-time salaries. There’s a decent chance that you, dear reader, make more money than some head college baseball coaches. Olympic sport assistants, or even football and basketball assistants at the low-majors, earn less than they’d make coaching high school.

On paper, the next largest expense category is usually scholarships and aid…but this math can get complicated. Yes, athletic departments will award tens of millions of dollars in athletic scholarships each season…but they’re paying that money to…the university. Most schools are not enrolled at 100% capacity, so the extra classroom desk and dorm space cost isn’t close to the on-paper cost of a scholarship. Universities may sometimes bill themselves for full price of tuition, even if the athletic scholarship is used on an in-state student, or perhaps somebody who might otherwise qualify for Pell Grants or other financial aid. The actual cost of this aid can be tricky to nail down.

Beyond salaries, physical infrastructure and scholarships, schools also need to pay for recruiting (staffers, travel, food, etc) athlete meals (and snacks), health insurance and medical care, game guarantees, athlete travel, and the costs of producing broadcasts. Throw in coach or administrator severance packages (i.e. paying Jimbo Fisher a gazillion dollars to not coach somewhere), and, starting this year, athlete revenue sharing…and you can see how a budget can easily climb to $200 million a year.

Athlete revenue sharing? How does that work?

Prior to 2025, athletic departments could give athletes scholarships. They could give financial awards to cover the full cost of attendance, give educational awards (Alston money), and other fringe benefits…but they couldn’t directly pay athletes for NIL or to otherwise compete athletically. All of that money had to come from either businesses (as actual NIL) or third-party donor groups (as fake NIL).

But as part of the settlement of House v NCAA and a few other antitrust cases, athletic departments can now pay athletes directly. This process is commonly referred to as “revenue sharing”, even if that isn’t technically what it is.

Here’s how it works. Starting this fall, schools can share up to $20.4 million in revenue with athletes. They can decide to share less than $20.4, or to not share any revenue at all. That revenue is “technically” for schools to purchase NIL rights for their athletes, even if it functionally serves as a talent acquisition or retention fee.

The $20.4 million figure came out of negotiations and calculations between the P4 conferences, NCAA, and plaintiff lawyers. Essentially, if you take the average of athletic department revenues among the biggest schools, subtract what schools spend on scholarships, athletic aid and other athlete development, you allegedly get to about $20.4 million. Think of that number as something of a salary cap.

Schools have to split that money up across their entire athletic department. The most common formulation right now is for schools to distribute roughly 75% of that pool to their football team, 15% to men’s basketball, 5% to women’s basketball, and 5% to everything else. But other schools have reached different calculations. Wisconsin, for example, has elite women’s volleyball and women’s hockey, but doesn’t have as strong a tradition in women’s hoops. They may decide to spend less on basketball and more elsewhere. UMass could decide to spend more on men’s hockey, or Cal State Fullerton to spend more on baseball.

Still with me so far? Good. Because it’s about to get stupid.

An athlete can earn above this proverbial cap via marketing deals. If an athlete signs a deal to promote Monster Energy Drinks on Instagram, or to appear in Nike TV commercials, or hawk autographs at the local mall, that can be all well and good. But the settlement requires athletes to report brand-based earnings above $600 to a clearinghouse, which will apply a Fair Market Value test to make sure athletes aren’t being paid huge deals for phony work deliverables in an attempt to circumvent the salary cap.

Essentially, everybody wants to prevent an athlete from earning a million bucks by signing a few autographs and speaking to one charity.

If these rules are strictly enforced, it would force schools to operate under the “cap” structure, driving down elite athlete compensation. Many industry professionals question whether these restrictions will stand up to additional court challenges, or whether anybody can actually enforce any of them. What the market will do this fall is very much an open question, depending on how various judges, politicians, and college administrators decide to act.

Tl;dr, how revenue sharing will actually work is still a pretty open question!

How do shoe deals work?

Every athletic department has an athletic apparel contract. While just about all of them have some things in common, the specifics will vary a lot, depending on the size of the athletic department.

As of right now, there are four companies who operate in the D1 space: Nike, Adidas, Under Armour, and New Balance (who sponsors Boston College, Maine and Denver). Currently, Nike has the largest market share in the college space.

The most important thing that every single school gets isn’t money. It’s product. Big companies like Nike and Adidas don’t just provide basketball shoes and jerseys for athletic departments…they’re providing everything from wristbands to polo shirts, hoodies to hats, socks to weight training gloves, soccer balls to sunglasses, and more. The sheer amount of stuff that an athletic department needs to outfit 16+ teams can be staggering, and big shoe companies manufacture most of it.

Most schools are given a certain amount of free or discounted product, as well as the rights to purchase additional stuff at a discounted rate. For example, in Nike’s contract with the University of New Mexico, the Lobos are given the right to buy up to $3 million worth of products at a 66% discount. For the University of New Hampshire, Nike gives a $100,000 annual credit to the athletic department. Depending on the company and the athletic department, some sort of combination of free stuff and discounted products make up the core of the contract.

Virtually every athletic department contract also contains performance incentives. Typically, the apparel company will provide additional product if their programs win conference titles, make or advance in the NCAA Tournaments, or win Coach of the Year awards. These incentives can be in straight cash, but typically, they’re just equipment vouchers. For example, if New Hampshire makes the NCAA Tournament in men’s or women’s basketball, Nike gives the school an extra $5,000 in equipment. For other sports, Nike will give a $2,500 voucher.

What isn’t very common is cold, hard cash. For the largest brands in college athletics, like Ohio State, Texas and Alabama, a shoe company will pay an annual licensing fee, in addition to free and discounted product. But for low, mid, and even some P5 schools, there’s usually no cash transfer whatsoever.

That wasn’t always the case. When Under Armour was trying to muscle in and capture market share from Adidas and Nike in the 2000s, the company “overpaid” via cash (and very generous product giveaways and customization options) to win business, providing cash to programs like Southern Illinois, Texas Tech, Cincinnati, and Cal that other shoe companies wouldn’t. When Under Armour’s business began to take a negative turn in the back half of the 2010s, those deals were either renegotiated, canceled, or let to expire, with future deals being less generous.

After COVID, increased labor and supply costs, a limited withdrawal from Under Armour and declining margins in the retail business, the general trend is for future apparel contracts to be less generous than ever before, outside the most elite brands.

What do the brands get?

One of the biggest advantages across all apparel contracts, from blue bloods to low-majors, is exclusivity. A school with a Nike agreement cannot have New Balance running shoes, Adidas warmup jackets or Under Armour soccer balls…if Nike makes it, the school has to use Nike stuff.

The apparel company is also getting money. Typically, schools aren’t getting enough free product to take care of all the school’s equipment needs, so they’ll need to fork over tens of thousands of dollars, or more, to buy more sneakers, warmup pants, polo shirts and more. Make no mistake, the big shoe brands make money from deals with SoCon and MAAC type institutions, even if they don’t sell a single item to fans in the retail market.

For larger brands, the apparel companies might not make as much money in sales to the university, but they’ll earn money in the retail world, as fans will want to pay premium prices for the official jerseys, shirts and other merchandise of good ol’ State U.

But brands also benefit in the marketing department.

Nike and Adidas are willing to pay incentive bonuses for teams making the NCAA Tournament, even in non-basketball sports, because they know that the Swoosh or the Three Stripes will appear in every stock photo, every broadcast and every story about those events. Apparel partners want to work with schools that will get on TV, play in front of big crowds, and generate exposure for their brands. That exposure, they hope, will translate into more sales on the consumer side, as well as increased traction in the high school and club worlds.

What does this mean for recruiting?

In the pre-NIL era, shoe companies had massive influence in the basketball recruiting world. A shoe company might sponsor a high school, club or AAU team, have employees funnel free product to prep recruits and coaches, and then navigate a recruit to one of the schools sponsored by that company. It would be uncommon for a high school kid who played for a Nike-sponsored AAU program to end up at an adidas-sponsored university. One of the best books on this dynamic was 1990’s Raw Recruits, although there are plenty of more modern examples.

The consumer market for football cleats or baseball equipment isn’t nearly as large as the basketball shoe market, so historically, major apparel companies had less direct influence on recruiting decisions in other sports.

I wouldn’t say that shoe companies or assorted affiliated parties have no influence in college basketball recruiting now, but the influence is a little diluted. For one, elite prep athletes don’t have to play college basketball if they don’t want to anymore. Athletes can play in NBA developmental league squads, play overseas, or pursue other professionalized options. In the NIL world, both donors and other large corporations can also wield direct recruiting influence in a “technically” above-board way, lessening the influence that a shoe company might have.

Of course, equipment does matter on some level for recruiting, because athletes may still have a personal preference for wearing a certain type of shoe.But in 2025 and beyond, the recruiting advantage of being a Nike school vs an adidas or UA school, generally speaking, is probably overblown a bit.

How do media deals work?

For the largest brands in college athletics, the single biggest check anybody is ever going to make comes from their media rights contract. But even for smaller schools that get very little (if any) money, their broadcast partner is one of the most important vendor relationships they have.

In the olden days of college sports, nobody had TV deals. The NCAA actually controlled everyone’s television rights, making sure that no single program got on television too much, or that the supply of college games in general wouldn’t become oversaturated.

This wasn’t as big a deal in the 1950s and 1960s, but by the late 1970s, the consumer market for sports on television had dramatically expanded. Many of the largest schools were frustrated with sharing revenue with tiny MAC schools, and felt they could earn dramatically more revenue and exposure by crafting their own deals. The NCAA refused, so the schools took them to court. The 1984 Supreme Court case Oklahoma v Board of Regents ended the NCAA monopoly on TV rights, setting the stage for conferences to sign their own media rights deals. This ushered in the modern era, where consumers can watch virtually any college sporting event they want.

The most common arrangement nowadays is for schools to relinquish all of their broadcast rights to a conference, who then in turn sells those combined rights to broadcast partners. A conference could have one partner, like ESPN, or multiple partners, like FOX/CBS/NBC. That partner then decides what games will be broadcast on linear channels (like ESPN or conference networks), vs streaming (like ESPN+, SECN+, etc).

While this is the most common arrangement in D-I, it isn’t the only one. The Coastal Athletic Conference, for example, has a media rights contract with FloSports, which streams athletic events behind a paywall. However, the CAA institutions retain local rebroadcast rights for football games, so a Towson football game could, theoretically, be shown for free on a local FOX affiliate, and then streamed out of state for a fee. The Summit League currently has a similar arrangement with North Dakota-based MIDCO Sports.

Occasionally, a broadcast partner will not elect to purchase all of a school or league’s media rights. Some broadcast inventory may be deemed too niche to profitably broadcast, for example, or a broadcast partner might not have the room to show everything. For many smaller sports, schools can sometimes have the ability to negotiate side deals with streaming partners, local television, or broadcast the games themselves on their websites. These side deals are generally not for very much money, but they can provide additional exposure.

How do broadcast companies figure out how much to pay for these deals? How do media rights valuations work?

This is a complicated process that is rapidly evolving, because consumer behavior is changing, thanks to cord cutting and demographic changes. But broadly speaking, media rights valuation depends on many of these factors.

Raw audience. What are the typical ratings for these athletic events, and what might those ratings be given the broadcast company’s time slots and reach? How many people are going to watch these events?

Market sizes. Do these institutions have fanbases that transcend their immediate local TV market? Do they bring exposure into other lucrative markets? How many potential new fans, or casual fans, could be activated? What else is competing for attention in those markets?

Audience demographics. Who is watching these events? Will the audience be confined to a particular geographic area, or is it national? Will the viewers be mostly men? Educated? Affluent? Are they part of more easily monetized demographic groups?

What is the competition for those media rights? Will other national broadcast partners be competing for these rights, or major tech companies? Will only one or two companies likely bid? Which competitor needs inventory and may be willing to overpay? Which potential partners have the most cash to burn?

How does this inventory fit with the strategic goals of the broadcast company, existing rights contracts, or future rights deals?

It’s important to think of all of these factors as related. A deal could very much be worth X amount of money in 2026 and Y in 2028, if more companies are able to bid in 2028, even if nothing else about the conference changes in those two years. Schools being in big cities but having tiny fanbases isn’t as useful in 2025 as it was in, say, 2010, when broadcast companies wanted to expand conference network distribution in traditional cable bundles. Different companies could value different leagues differently.

Generally speaking, rights for football broadcasts are dramatically more valuable than rights for basketball broadcasts, even though there are always more basketball games than football games. Generally speaking, Olympic sport quality and audience also typically doesn’t influence media rights contracts in a meaningful way. But there are always exceptions.

What else matters in these deals besides cash and ratings?

At the mid-major level, it’s critical for schools to consider who pays for the production costs for broadcasts. When ESPN signs a smaller league for ESPN+, the four letter network generally isn’t paying for the broadcast costs of the event. The mid-major is responsible for the cameras, the announcers, the trucks, and other physical equipment. ESPN may designate a minimum broadcast standard, but they’re not sending staffers from Bristol to actually man the cameras and produce the game.

That can mean schools have to spend a significant amount of money on building their own infrastructure before they cash a single check from ESPN, or anybody else. At the mid-major and low-major level, broadcast rights are functionally not even a revenue source. Any money that comes in has to be reinvested right back in the product.

That’s why it’s very common for undergraduates to play huge roles in college sports broadcasts, even at larger schools. Most D-I schools essentially have little TV studios on their campus to handle the production of sporting events, with hookups for the few times that a national outlet comes to town with their own equipment and talent.

Schools also deeply care about exposure and access. One of the reasons ESPN is so popular a partner isn’t because they always pay the most money in rights fees, (they don’t), but because ESPN is so well known and easy to access. If almost every D-1 conference has at least some type of partnership with ESPN, then fans are more likely to already have access to ESPN+ or ESPN networks. A CBS, FloSports, NBC, CW or other challenger companies may offer more money, but many schools are concerned about how a lack of exposure could hurt them in recruiting, postseason access, and marketing efforts.

This is also a reason why some D-II and D-III schools decide not to sign any media rights contracts, even if they could badly use the revenue. Non-D1 broadcast deals usually involve paywalls, and with audiences already small, some schools believe the exposure tradeoff isn’t worth the revenue. Other conferences have reached a different conclusion.

There may also be other considerations. Will a broadcast company create student internship opportunities? Will they let schools sell their own international broadcast rights? How flexible will the broadcaster be about tip-off times or dates? Can they help with athletic scheduling? What other doors can they open for an athletic department?

The whole process is complicated, which is why broadcast companies and conferences often rely on consultants and marketing agencies to help both sides figure out media rights valuations, and the best way for all parties to get the most out of those partnerships.

Is this everything?

Not even close!

We didn’t get a chance to talk about how coaching searches actually work, how search firms work, how athletic departments build development teams, how the video game industry intersects with college sports, or any of the dozens of other components of college sports operate. That, my friends, would be a book, not a PDF or static webpage.

But I hope it’s enough to get you started. You can’t begin to understand why departments, conferences and the NCAA makes the decisions they make without understanding how schools earn and spend their money. And many of the other headlines you read won’t make sense without understanding how college sports is, and isn’t, a conventional big business.

Want to dig in more?

Grab a monthly or annual subscription here. With a subscription, you’ll get,

FOUR newsletters a week, AND access to our entire archives. That’s like, five books worth (and five years) of Extra Points newsletters.

Access to Athletic Director Simulator 4000, our computer game where YOU get to be an athletic director

A free ebook version of my book, What If?

The warm feeling in your heart that comes from supporting independent media