Good morning, and thanks for spending part of your day with Extra Points.

If you’ve enjoyed these newsletters, why not share them with your friends? Better yet, why not show your support for Extra Points with a paid subscription?

A paid subscription gives you four newsletters a week, for just $7 bucks a month, or $70 for the year.

If you’re a student that would like to subscribe but don’t have the cash, or work for a school and would like Extra Points subscriptions in bulk, drop me a line at [email protected], and I’ll be happy to help you out.

Today, I want to pass the mic over to Katie Lever, a former athlete at Western Kentucky, who is currently pursuing a PhD at the University of Texas. I think her experiences with the NCAA will help provide some important context around the athlete activism we’re seeing right now, and how that athletic scholarship might not be as secure as you might think.

By Katie Lever

If you’re a fan of athletic activism (or if you just really, really love watching the NCAA burn), you’re probably pretty excited right now.

It’s been just over a week, now, since a Pac-12 players group threatened to boycott the 2020 season if their list of safety and racial justice demands were not met, setting in motion a national athlete advocacy movement that college sports has never seen. Three days later, Big Ten players released a list of player safety requests. Then, the Mountain West and the AAC joined in. Perhaps the biggest move happened late Sunday night, when a group of Power Five athlete representatives published a statement that included a request to form a College Football Players Association. At long last, these athletes are organizing at a national level and, as a former college athlete, it’s been cool to watch. But this recent wave of activism also begs the question: What took so long?

It’s always been risky for athletes to organize because, in spite of NCAA rules that regulate the cancellation, reduction, and non-renewal of athletic aid, coaches can way too easily use grant-in-aid scholarships as a cudgel against athletes who don’t fall in line. Things seem to be coming to a boiling point now, but financial intimidation has always been an easy way for coaches to silence their athletes.

One of the most pervasive myths within the NCAA is that athletic scholarships are guaranteed for four years. For a long time, they weren’t allowed at all. From 1973 to 2012, the NCAA enforced a multiyear scholarship ban, which mandated that all athletic scholarships be awarded on a year-to-year basis and renewed (or not) in the offseason. The NCAA lifted the multiyear ban in 2012, but its ruling fell short of requiring universities to award scholarships that last more than one academic year at a time. Today, multiyear scholarships are still incredibly rare.

Let’s rewind to 2014 to understand why.

That’s the year the NCAA granted the Power 5 –– ACC, Big 10, Big 12, Pac-12, and the SEC—an area of autonomy over certain NCAA policies. Basically, this means that the Power 5 schools have the ability to create some of their own rules, including those governing certain aspects of financial aid. Non-autonomy conferences (the mid-major universities that make up the vast majority of the NCAA) are allowed to adopt autonomy conference rules if they so choose, or they can default to NCAA policies.

The voting-in of new autonomy policies each year is a fairly simple (and relatively democratic) process: each Power 5 university gets a vote, along with three athletes selected from each conference. That equates to 65 schools and 15 athletes for a total of 80 votes in legislative decision-making at the Power 5 level. In 2015, the autonomy representatives voted to prohibit coaches from non-renewing, reducing, or cancelling athletic scholarships for athletically-related reasons (injuries, illness, low performance, etc.). The measure passed by two votes, thanks in large part to the athlete representatives serving on the panel; these autonomy rules were written into NCAA policy for the 2015-16 season.

Since 2015, the Division I Manual has divided some sections of policy between autonomy and non-autonomy rules, including the section on the cancellation and nonrenewal of athletic aid. You would think that would provide schools with a pretty even split of bylaws: one for autonomy schools to follow and another for non-autonomy schools to follow. And that’s how the D-I Manual reads, with autonomy policies denoted with a bracketed A.

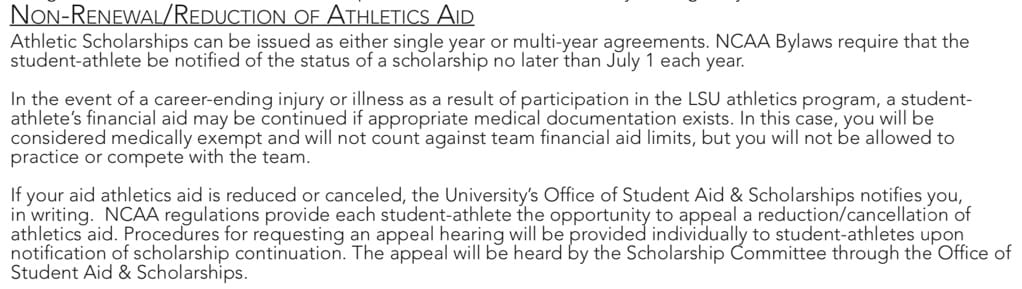

These policies, however, are much more complicated in practice than on paper and, to understand how they actually play out, you have to sift through the compliance manuals of each member school, as policies can vary by institution. A quick skim of autonomy school handbooks quickly debunks the myth that all athletic scholarships are guaranteed, multiyear deals. Take a look at this excerpt from LSU’s Student-Athlete Handbook, for example:

It clearly states that “athletic scholarships can be issued as either single year or multiyear agreements.” The handbook also notes that scholarships can (but do not have to be) continued if an athlete suffers a “career-ending” injury, so long as “appropriate medical documentation exists.” That’s not necessarily a guarantee, and it makes for an uncomfortable amount of gray area for injured athletes.

Now, take a look at a similar excerpt from the University of Kentucky’s Student-Athlete Handbook, keeping in mind the autonomy conferences’ 2015 ruling that athletic scholarships can’t be revoked due to low performance:

UK’s handbook strongly suggests that athletic scholarships can, in fact, be revoked for athletically-related reasons, in direct contradiction to the 2015 autonomy ruling written into the D-I Manual. However, the phrasing of the NCAA’s “area of autonomy” might explain the legality of Kentucky’s performance-based scholarship rule:

The above excerpt states that the NCAA grants “legislative flexibility” to the Power 5 and “its member schools.” Considering that the SEC Manual contains no hard-and-fast rules about the revocation or nonrenewal of scholarships for performance reasons, my best interpretation of UK’s policy is: the SEC is an autonomy conference, and conference bylaws don’t explicitly mandate autonomy rules, so UK is taking advantage of its legislative flexibility in crafting its own scholarship policies. Otherwise, UK is committing an NCAA infraction in broad daylight.

For the record, I’ve reviewed every publically available compliance manual in the SEC, and none of them explicitly prevent scholarship revocation due to injury or athletic performance, after the period of award. It’s entirely reasonable to believe that every school in the SEC is operating under UK’s rules—they’re just not stating it so brazenly.

Is this confusing at all? Imagine being a high school prospect (a legal minor) trying to navigate this process.

Now, let’s look at Western Kentucky University’s Student-Athlete Handbook, which follows non-autonomy policies. The scholarship rules here are much more cut and dry:

WKU clearly says that scholarships are “awarded and renewable on a year-by-year basis” at the discretion of a head coach. The clarity can be a double-edged sword: scholarships of non-autonomy athletes can, with certainty, be reduced, canceled, or non-renewed for virtually any reason, which is problematic for athletes. But at least the athletic departments are more transparent about it.

Here’s how this policy can work out in practice.

I ran track and cross country for WKU from 2012-2017. My freshman year was pretty abysmal, as I adjusted to athletic and academic time demands of a D-I athlete. I prioritized my academics, and my track performances suffered. As a result, right as I was boarding my team’s bus after a subpar conference meet, my coach pulled me aside and told me: “Katie, that was your warning year. If you don’t perform next season, I’m pulling your scholarship.” Thankfully, I surged as a sophomore and maintained my scholarship, but the “warning year” mentality never quite went away for me.

To be clear, what my (non-autonomy) coach did is also perfectly legal at the autonomy level, because there are no NCAA rules that prohibit coaches from threatening to pull athletic scholarships. That’s why Rutgers head softball coach Kristen Butler, who, last year, was accused of threatening to revoke her athletes' scholarships, among other abuse allegations, still has a job. There are no rules against this in the D-I Manual.

Even coaches who are disciplined for this behavior can go largely unpunished within the NCAA. Take former Alabama baseball coach Greg Goff, who, in 2017, was released by the university after his players reported him for attempting to revoke their scholarships for athletics reasons. Two months later, Goff was hired by Purdue University.

Now, even with all the ground we’ve covered, there are still a couple of financial aid stipulations to keep in mind, which help explain why college athletes might suppress their concerns of, say, catching COVID-19, in order to train and compete. When policies read that scholarships cannot be revoked “during the period of award,” keep in mind that the typical period of award is one academic year. This is one reason why the NCAA’s coronavirus "safeguard" announcement last week was problematically lackluster. The NCAA asserted that an “athletics scholarship commitment must be honored,” even if an athlete opts out over pandemic-related concerns. But since athletic scholarships don’t have to be multiyear deals, a coach could follow the NCAA’s mandate by simply waiting after the academic year to pull a scholarship from a player who opts out if that athlete is on a renewable scholarship.

Coronavirus aside, pretty much anything goes in the offseason financial aid-wise, because, according to Bylaw 15.3.5 of the D-I Manual, athletic aid can be reduced or cancelled (even during the period of award) if an athlete violates a team policy. There are no NCAA policies that regulate team rules, so coaches are essentially free to dictate whatever they want. If coaches have team policies that even implicitly staunch activism, organizing, or speaking out against their school, any of those athletes who are supporting player movements right now are risking their scholarships.

Even under non-pandemic conditions, it takes tremendous courage for college athletes to organize, and the precariousness of athletic scholarships only amplifies the risk of doing so. That’s just one of the many reasons college athletes need employee protections and rights to their NILs: one of the simplest ways for coaches to censor entire teams is to threaten athletes’ livelihoods, and it’s too easy to do that within the NCAA’s current financial aid legislation. College athletes are controllable when they are financially unstable, and their scholarships often function more like puppet strings than a means to a free education.

Katie Lever is a former Division I athlete and current doctoral student at the University of Texas, where she studies NCAA rhetoric and advocates for college athletes. Find her on Twitter @leverfever

Additional questions, comments, business inquires, mailbag ideas and more can be sent to [email protected], or to @MattBrownEP on Twitter.

Featured photo by mj0007 / Getty Images

The Intercollegiate and Extra Points are proud to partner with the College Sport Research Institute, an academic center housed within the Department of Sport and Entertainment Management at the University of South Carolina. CSRI’s mission is to encourage and support interdisciplinary and inter-university collaborative college-sport research, serve as a research consortium for college-sport researchers from across the United States, and disseminate college-sport research results to academics, college-sport practitioners and the general public. You can learn more by visiting CSRI’s website.