Good morning, and thanks for spending part of your day with Extra Points.

Back in May, we announced a new content series with Teamworks on how General Managers work. We’ve previously published newsletters that covered the specific skills needed to be successful as a P4 CFB GM, what mid-major basketball GMs actually do, ,what types of technology platforms GMs use to actually DO the job, and why a former AD decided to take a mid-major GM job.

I think all of those stories examined the GM Job Title…what kind of person takes on that role, what skills are required to be successful, how successful measured, and how the job actually works. Those are all important questions, and worthy of being investigated even after this series has ended.

But today, I want to focus a little more on the framework that GMs have to operate under…the House Settlement.

Earlier this week, I wrote about how the settlement terms essentially function as a college sports collective bargaining agreement (CBA), only without the labor actually negotiating with the management part. The settlement creates a salary cap, ($20.5 in direct payments from schools to athletes for 2025-2026), governs how payments work outside the cap, and creates a body responsible for enforcing those rules.

Schools will try to figure out how to be successful in this era based on how well they can evaluate talent, how well they can develop alternative revenue streams to support their budgets, how well they can distribute their resources efficiently, and how well they can develop the players they already have.

But there’s another element that isn’t getting a lot of attention yet. How will schools look to structure those deals around the salary cap rules?

Lets consider the following scenario, laid out by Noah Henderson, the Director of the Sport Management Program at Loyola-Chicago.

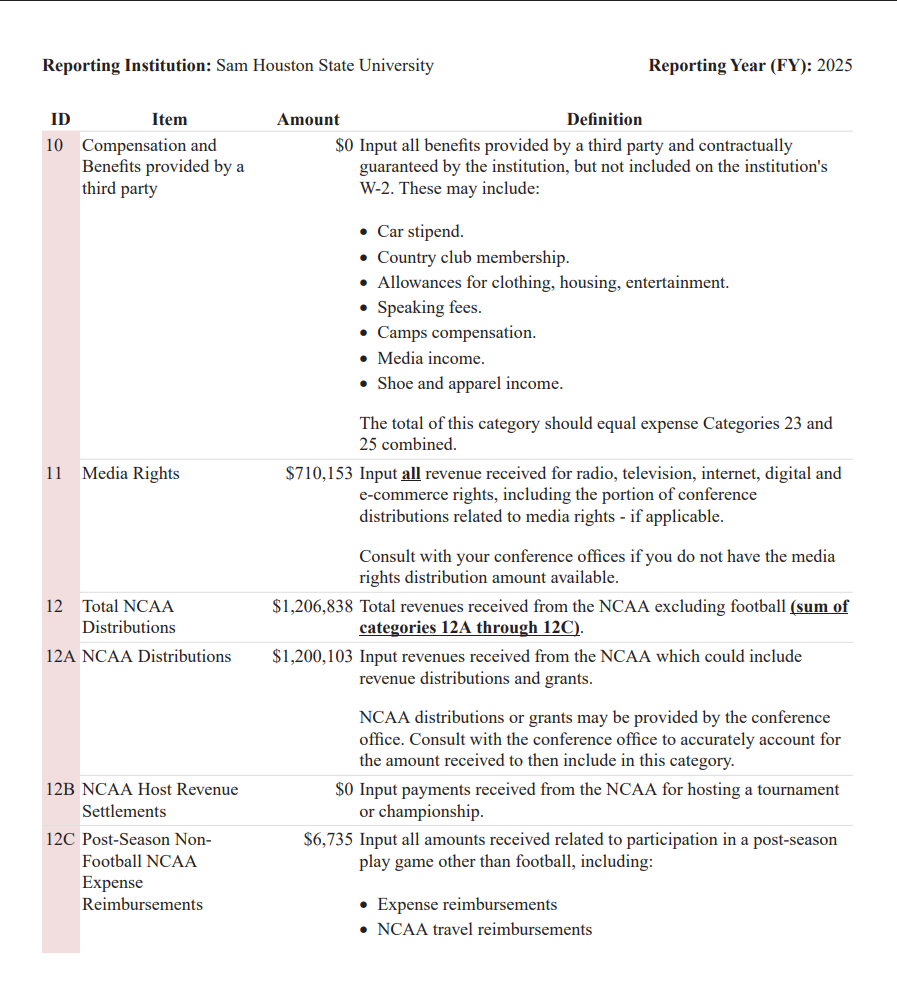

The current $20.5 million “cap” is calculated as 22% of the “average shared revenue”, as reported on the annual MFRS reports, of the power conference programs. If I am understanding the current structure correctly, that cap will increase by 4% for the 2026-2027 season, and by another 4% for 2027-2028, before being recalculated. There will also be recalculations in year 7 and year 10.

But college athletic department revenues do not increase (or decrease) at a completely uniform rate. If a program is going to complete a stadium renovation in 2026 that will allow the school to sell more luxury seating, it’s probably that ticketing revenue will have a meaningful increase in that fiscal year. If you know you’re only going to have six home games, well, you’ll probably have less income that year.

Here’s Henderson:

While the $20.5 million figure is a hard cap on paper, the ability for schools to shift budget allocation year-to-year between teams allows athletic departments to tweak team-wide budgets to account for changing priorities or invest in a team that seems “one piece away.”

These three recalculations will be based on Membership Financial Reporting System (MFRS) reports, which aggregate revenue streams from institutions within the Pac-12, Big Ten, Big 12, SEC, and ACC, including football-independent Notre Dame.2

Given the trajectory of media rights valuations and a heightened focus on revenue generation to offset the burden of athlete compensation, these recalibration years could yield significant spikes to schools' revenue-sharing caps.

Translation: perhaps a team could hypothetically decide to back load a contract to line up with an expected “spike” in the House salary cap, thus allowing them to give more money to a player without compromising future financial flexibility.

The NBA, as Henderson pointed out, did not always have a smooth and predictable system for calculating the salary cap, meaning it could dramatically spike at any time if revenues increased. In 2016, the cap suddenly jumped by over 30%. That led to such famous contracts as Allen Crabbe AND Evan Turner getting four years at $75 million from the Trail Blazers, or Luol Deng getting over $70 million from the Lakers. Had NBA teams been better at projecting future revenues, those deals would have looked very different.

It’s entirely possible that in five years, we’ll look back at the rush to front load as many player contracts as possible with collective money before the ratification of House as something similar…when players of average production could command transfer portal payments well into the seven figures.

Of course, it’s not a perfect one-to-one comparison between the pros and college. Bad contracts in college can’t be traded, and programs can’t easily “rent’ out their salary cap space to other teams for future assets. And since college athletes are younger and less proven than their counterparts in the NBA and NFL, schools may be more hesitant to offer long enough deals to really take advantage of the benefits of “cap smoothing” larger contracts against cap spikes.

So there may be other vehicles used to optimize program spending.

Let’s consider the NBA again. Sometimes, a veteran team looking to compete for a championship that year won’t place the same value on draft assets or young players as other franchises. Rather than tie up roster spots (and salary obligations) with prospects who likely won’t get the chance to play that season, some NBA teams would be more likely to draft International players who could play at a different level, actually secure playing time, and free up cap and roster space for the here and now.

You can’t exactly do that in college athletics, but a similar plan might be for a larger program to use a smaller school (like a G5 or an FCS squad) as something of a feeder program. A player that could have potential to develop into a Big Ten player down the road might be encouraged to play at a friendly Missouri Valley Football Conference program as a freshman. If the player develops well, then Minnesota or Purdue could swoop in and give the player a significant raise. The development costs, such as they are, would count against the “cap” of South Dakota, not Minnesota.

In international soccer, this system works because the smaller club can get a transfer fee. Since contract buyouts are not permitted to be used to spend over the cap, there isn’t nearly as much utility in trying to develop players in order for big programs to spend buyouts. But perhaps a more informal relationship could be established where South Dakota might benefit from getting players they wouldn’t otherwise get, while Minnesota gets to develop younger talent without overspending their $20.5 million.

There’s also still room to sort out what the best practices of payment structures will look like. Is it better to pay the bulk of a contract length up front, in order to secure the athlete? Will athletes tolerate incentive-laden deals, and will those continue to pass scrutiny as “being for NIL rights” if the payment amounts are increasingly set to on-field specific benchmarks? Without a CBA or historical precedent, it will take a minute for water to find its level.

In the future, schools will likely need to pay almost as much attention to how they decide to pay players as they do in figuring out who to pay. Can payments be stretched out over multiple years? What sort of buyout language sufficiently protects the school without becoming unpalatable to an athlete and his representation? To what extent can “fair market value” NIL deals be scaled and standardized, allowing athletes to earn above the cap? What creative loopholes will CPAs and lawyers find?

You can’t completely steal the playbook from the Philadelphia Eagles or Oklahoma City Thunder. They’re not playing by the same rules as college programs. But there may be clues in how the professional front offices have made their math math as programs prepare to build out their budgets not just for this season, but for the years to come.